The Writer's Almanac from Saturday, November 9, 2013

"Greenwich" by Kirsten Dierking, from Tether. © Spout Press, 2013.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2013

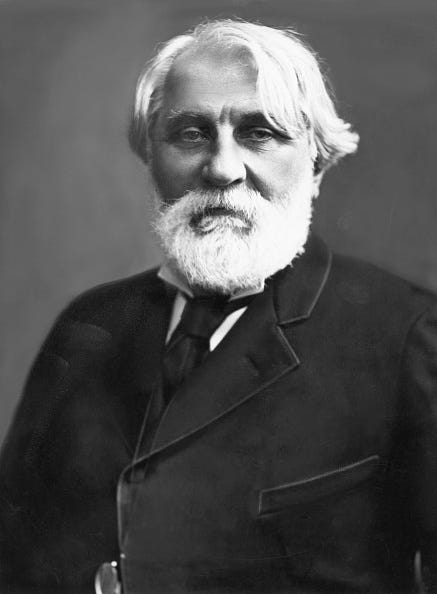

It's the birthday of Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, born in Orel, Russia (1818), best known for his novel Fathers and Sons (1862). He grew up near Moscow, where his mother was a wealthy landowner. But as a young man, he went away to study in Berlin. The experience of leaving Russia changed his life. He said, "I threw myself head first into the 'German Sea,' in which I was ... cleansed and reborn, and when I finally surfaced from its waves, I was a 'Westernist' and remained one forever." From a distance, he began to think of Russia as a barbarous place where serfs were kept as slaves and treated as animals. He would devote the rest of his life to exposing the inhumanity of serfdom.

Fathers and Sons, Turgenev's masterpiece, is about the conflict between two generations, the conservative elder generation and the radical youths who want to do away with tradition and create a new social order.

It's the birthday of poet Anne Sexton, born in Newton, Massachusetts (1928). She said: "As a young child, I was locked in my room until the age of five. After that, at school, I did not understand the people who were my size or even the larger ones. At home, or away from it, people seemed out of reach. Thus I hid in fairy tales and read them daily like a prayer-book. Any book was closer than a person."

It was on this day in 1967 that the first issue of Rolling Stone was published. It was started by 21-year-old Jann Wenner, who dropped out of Berkeley and borrowed $7,500 from family members and from people on a mailing list that he stole from a local radio station, and with that money, he managed to put together a magazine. The cover of the first issue featured John Lennon, and in it, Wenner wrote, "Rolling Stone is not just about music, but also about the things and attitudes that the music embraces." He printed 40,000 copies, and 34,000 were returned unsold. But soon Rolling Stone had a devoted group of readers, partly because there were some great writers there. Probably the most famous of these journalists was Hunter S. Thompson, who showed up at Jann Wenner's office in 1970 with a case of beer and an offer to write for Rolling Stone. The next year, he serialized Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in the magazine's pages. Today, Rolling Stone has a circulation of about 1.4 million.

Today is the anniversary of Kristallnacht, the night in 1938 when German Nazis coordinated a nationwide attack on Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues. The attack was inspired by the murder of a German diplomat by a Jew in Paris. When Hitler heard the news, he got the idea to stage a mass uprising in response. He and Joseph Goebbels contacted storm troopers around the country and told them to attack Jewish buildings, but to make the attacks look like spontaneous demonstrations. The police were told not to interfere with the demonstrators, but instead to arrest the Jewish victims. Firefighters were told only to put out fires in any adjacent Aryan properties. Everyone cooperated.

In all, more than 1,000 synagogues were burned or destroyed. Rioters looted about 7,500 Jewish businesses and vandalized Jewish hospitals, homes, schools, and cemeteries. Many of the attackers were neighbors of the victims. The Nazis confiscated any compensation claims that insurance companies paid to Jews. They also imposed a huge collective fine on the Jewish community for having supposedly incited the violence. The event was used to justify barring Jews from schools and most public places, and forcing them to adhere to new curfews. In the days following, thousands of Jews were sent to concentration camps.

The event was called Kristallnacht, which means, "Night of Broken Glass." It's generally considered the official beginning of the Holocaust. Before that night, the Nazis had killed people secretly and individually. After Kristallnacht, the Nazis felt free to persecute the Jews openly, because they knew no one would stop them.

It was on this day in 1989 that the Berlin Wall came down in Germany. After World War II, Germany was divided into four parts, each occupied by one of the major Allied powers — France, England, the United States, and the Soviet Union. It didn't take long for relations between the Soviet Union and the other Allies to deteriorate, at which point the Soviet portion became East Germany, and the rest became West Germany. Berlin was also controlled by all four powers, so it was divided similarly to the rest of the country — into East and West Berlin — even though it was entirely surrounded by East Germany.

To stop refugees from fleeing to the West, the East Germans built a barbed-wire fence and established checkpoints along the border between East and West Germany. However, for a long time there was no physical barrier between the two halves of Berlin, so refugees went from East to West Berlin — and from there, to the rest of Western Europe. By 1961, more than 3.5 million East Germans had fled — more than 20 percent of the entire population. So the East Germans decided to put up a wall in the city. They began construction in the middle of the night and surrounded West Berlin. For 28 years, the Berlin Wall stopped emigration from the Eastern Bloc to Western Europe. Many people were killed trying to cross.

In the late 1980s, things changed. With Mikhail Gorbachev at the helm, the Soviet Union became more liberal. In 1989, Poland had the first free elections in the Eastern Bloc, and the Communists lost. That fall, Hungary opened its border with Austria. On November 4th, more than half a million protestors turned out in East Berlin, chanting Wir sind das Volk — "We are the people" — and demanding reforms.

November 9th, 1989, was a gray, cold Thursday in Berlin. East German officials made a last-minute decision to loosen travel restrictions for their citizens, hoping to quiet the unrest. An official named Günter Schabowski was in charge of giving regular press conferences for the government, and right before the press conference, he was handed a note with the news that East Berliners would be allowed to cross to West Berlin if they had permission. He didn't know anything else about it, so he just read the note aloud. When a journalist asked him when the order would take effect, he had no idea, but after a hesitation, he mumbled his best guess: that it would take effect immediately.

Schabowski's press conference was broadcast on all the nightly news channels, with news anchors declaring triumphantly that safe passage was now open between the two sides. Thousands of East Berliners thronged to the wall, demanding to be let through. Television crews covered the activity live, bringing even more people out on the streets. Frantic and confused border guards kept trying to telephone their superiors, but no official wanted to be responsible for issuing an order to open fire; meanwhile, the crowds were growing larger. Finally, the guards had no choice but to let the mob through. West Berliners had also heard the news on television, and there were crowds waiting on the west side of the wall with cheers and champagne. Restaurants offered East Berliners free meals, a soccer club gave out free tickets to their game, and individual West Berliners called their local TV station with offers of free lodging, beds, and theater tickets. The West German government gave East Germans "greeting money," about $55 to spend as they chose in the much-wealthier West.

In the days that followed, Germans from both sides tore down the wall with hammers, pickaxes, and screwdrivers. The East German government announced that it would be opening 10 new border crossings, and army bulldozers drilled into the wall to create them. Although they were technically creating new crossings, not tearing down the wall, the general consensus was that the wall was crumbling. Crowds waited for hours for the bulldozers, and then showered the drivers with flowers before picking up pieces of the wall as souvenirs. The East German protest chant of Wir sind das Volk, — "We are the people" — was changed to Wir sind ein Volk — "We are one people."

On Christmas morning of 1989, six weeks after the opening of the Berlin Wall, 71-year-old Leonard Bernstein conducted a performance in Berlin of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, with the words "Ode to Joy" changed to "Ode to Freedom." His orchestra and choir were made up of citizens from East and West Germany, France, the Soviet Union, England, and the United States. It was the first Christmas in decades that East and West Berliners could cross freely between the sides of the city, and many did so that day, waiting in lines for hours to get across. East Berliners enjoyed sausages from street vendors in West Berlin, while West Berliners packed into shops and restaurants on East Berlin's most famous street, Unter den Linden.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

CLICK HERE for more information!

In this very ominous time when so many are fearful that history is repeating itself in the wrong direction, “we are the people” is what we need to remember.