The Writer's Almanac from Sunday, November 3, 2013

"Harmony" by Stuart Kestenbaum, from Pilgrimage. © Coyote Love Press, 1990.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2013

It's the birthday of the photographer Walker Evans, born in St. Louis, Missouri (1903). His father was a wealthy advertising executive, and Evans spent most of his childhood in boarding schools. He dropped out of college after one year and went off to Paris to become a writer. He spent a lot of his time at Sylvia Beach's bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, and one day he saw James Joyce there, but he was too shy to introduce himself. He didn't meet any other important writers, and his own writing didn't amount to much. He said, "I wanted so much to write that I couldn't write a word."

He went back to the United States, feeling like a failure, but one day he picked up a camera and started taking pictures. One of the first pictures he took in America was of the parade honoring Lindbergh's flight in 1927. Instead of focusing on the parade itself, he focused on the street the parade had just passed through, littered with crumpled handbills and confetti.

He had felt so reverential toward literature that it blocked him up, but with a camera he could point and capture anything he wanted. The popular photography of the day was highly stylized, so Evans decided to go in the opposite direction, to take pictures of ordinary, unpretentious things. He said, "If the thing is there, why, there it is."He photographed storefronts and signs with marquee lights, blurred views from speeding trains, old office furniture, and common tools. He took pictures of people in the New York City subways with a camera hidden in his winter coat.

Evans especially loved photographing bedrooms: farmers' bedrooms, bohemian bedrooms, middle-class bedrooms. He'd photograph what people had on their mantles, on their dressers, and in their dresser drawers. By the early 1930s, he was one of the most celebrated photographers in the United States. In 1933, he was given the first one-man photographic exhibition by the new Museum of Modern Art.

In the summer of 1936, he went down to Greensboro, Alabama, to photograph tenant farmers struggling through the Great Depression. He spent weeks there, with the journalist James Agee, photographing the Burroughs family, the Fieldses, and the Tingle family at work on their farms and in their ramshackle homes.

At first, he was uncomfortable with the idea of taking pictures of such desperate people, but James Agee persuaded him that their job was show how noble these people were despite their circumstances. When Evans and Agee said goodbye at the end of their work, the farmers wept. The photographs, with Agee's text, were published in the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). They are among the most famous images of the Great Depression.

Walker Evans said, "Fine photography is literature, and it should be."

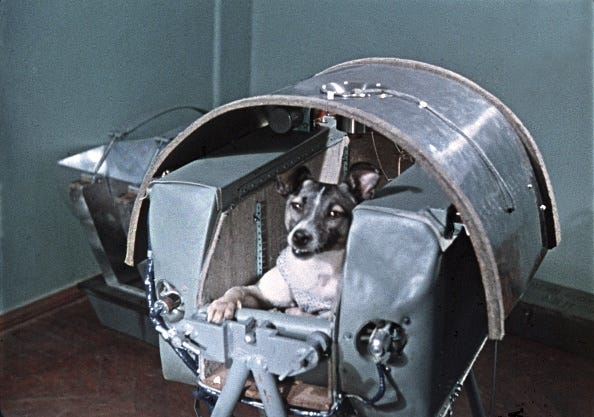

A little dog named Laika was launched into space aboard Sputnik 2 on this date in 1957. The mission for Sputnik 2 was to determine if a living animal could survive being launched into orbit. Laika was a stray that had been picked up from the Moscow streets, a 13-pound mutt with perky ears, a curly tail, and uncertain ancestry. She probably had a little spitz or terrier in her family tree, maybe a Siberian husky or even a beagle here and there. She was three years old, a good-natured dog that came to have several nicknames: Lemon, Little Curly, and Little Bug. Her name, Laika, means "barker" and was a generic term applied to all spitz-type dogs. The American press called her "Muttnik." The Soviet space program deliberately chose strays for their missions because it was felt that they had proven themselves to be hardy, having already survived deprivation, extremes in temperature, and stress.

Laika was the first animal to orbit the Earth. She was harnessed inside a snug, padded cabin with some ability to move, but not much. The capsule was climate-controlled, and she had access to food and water, and there were electrodes monitoring her vital signs, but everyone knew the capsule was not designed to return to Earth in one piece. Knowing that Laika had little time to live, one of the scientists took her home to play with his children a few days before the launch.

For many years, reports of her death were inconsistent; one report said that she lived for six days, until her oxygen ran out. The Soviet government insisted she had been euthanized via a pre-planned poisoned food portion prior to that, to make her death more humane. In 1999, it was revealed that vital signs ceased to be transmitted about five to seven hours after the launch, possibly because the booster rocket failed to separate from the capsule, causing the thermal control system to malfunction and the cabin to become unbearably hot.

In 1998, after the fall of the Soviet Union, one of the scientists spoke of his regret for Laika. He said: "Work with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I'm sorry about it. We shouldn't have done it ... We did not learn enough from this mission to justify the death of the dog."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

The story of Laika breaks my heart.

How very appropriate this one is, Garrison. Thank you for giving us your wisdom and sharing such great stories. The poem about harmony seems even more relevant now.