The Writer's Almanac from Wednesday, November 22, 2017

“Winter Grace” by Patricia Fargnoli from Hallowed. © Tupelo Press, 2017.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on this date in 1963.

Kennedy hadn’t formally announced that he was going to run for re-election in 1964, but he was laying the groundwork. He embarked on a tour out west to sound out potential themes — like education and national security — that he could center his future campaign on. Florida and Texas were key states that he would need to win, so he planned to visit both states. He and his wife Jackie, who had been out of the public eye since the death of their son Patrick in August, started in San Antonio, then moved on to Houston and Fort Worth, where they spent the night of November 21st. After a few public appearances in rainy Fort Worth on the morning of the 22nd, the Kennedys took a 13-minute flight to Dallas’s Love Field. The rain had stopped, so the plastic bubble was left off the top of the convertible limousine that carried the Kennedys, Governor John Connally, and his wife, Nellie. The party embarked on a 10-mile route that would take them to the Trade Mart, where the president was scheduled to speak at a luncheon.

But, of course, the motorcade didn’t make it to Trade Mart. As they drove through Dealey Plaza, Lee Harvey Oswald opened fire from a sixth-floor window in the Texas School Book Depository. The president was rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital with gunshot wounds to his head and neck. He was pronounced dead at 1:00 p.m., and Vice President Lyndon Johnson took the oath of office at 2:38. President Kennedy was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery on Monday, November 25 — his son John Junior’s third birthday.

Last month, President Trump ordered the release of nearly 3,000 records related to the assassination. The National Archives will release them in batches over the next few months.

It’s the birthday of Charles de Gaulle, born in Lille, France (1890). He was general and president of France from 1959 to 1969. De Gaulle was a brigadier general in 1940 when he found himself in London after escaping France, which had just fallen to German forces. In an impassioned speech on British radio, he famously said: “But has the last word been said? Must we abandon all hope? Is our defeat final and irremediable? To those questions I answer — No! For remember this, France is not alone. She is not alone. She is not alone. Behind her is a vast empire, and she can make common cause with the British Empire, which commands the seas and is continuing the struggle. I, General de Gaulle, now in London, invite French officers and men who are at present in British soil, or may be in the future, with or without their arms; I invite engineers and skilled workmen from the armaments factories who are at present on British soil, or may be in the future, to get in touch with me. Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and shall not die.”

The French government declared him a traitor and sentenced him to death for treason, but de Gaulle didn’t give up. His exhortation to “Free France” led to the formation of the Free French Forces, which became the fourth-largest Allied army in Europe by war’s end. They participated in the Normandy landings and the invasion of Germany and eventually liberated Paris.

Military life was ingrained in de Gaulle from childhood. His father was a professor who taught him the history of France, and de Gaulle raced through military history books, reenacting key battles. His uncle, also named Charles de Gaulle, had written a book calling for the union of the Breton, Scots, Irish, and Welsh peoples. In a journal, the young de Gaulle carefully copied a sentence from his uncle’s book: “In a camp, surprised by enemy attack under cover of night, where each man is fighting alone, in dark confusion, no one asks for the grade or rank of the man who lifts up the standard and makes the first call to rally for resistance.”

Charles de Gaulle was known for his regal bearing and fastidious nature, so much so that his imperiousness became a kind of running joke for the citizens of France. A popular gag imagined de Gaulle’s wife, Yvonne, returning from shopping and exclaiming, “God, I am tired.” Her husband is purported to have replied, “I have often told you, my dear, it was sufficient in private if you addressed me as ‘Monsieur le President.’”

He was frugal and at banquets, his quick manner of eating became legendary: plates were snatched away while still full, and de Gaulle spurned fruit, thinking it took too long to peel. He found cheese too small to be of use and once quipped, “How can you govern a country that has 246 varieties of cheese?” State banquets rarely lasted even an hour.

He meticulously prepared for televised speeches, practicing his lines in a mirror and taking lessons from an actor. Winston Churchill, the prime minister of England, once told President Roosevelt, “De Gaulle may be a good man, but he has a messianic complex.” About Winston Churchill, de Gaulle said dryly: “When I am right, I get angry. Churchill gets angry when he is wrong. We are angry at each other much of the time.”

Charles de Gaulle once said, “I cannot prevent the French from being French.”

On August 25, 1944, Charles de Gaulle entered Paris, which had been liberated the day before. In a famous speech, he cried: “This duty of war, all the men who are here and all those who hear us in France know that it demands national unity. We, who have lived the greatest hours of our History, we have nothing else to wish than to show ourselves, up to the end, worthy of France. Long live France!”

Today is the birthday of the author best known by her pen name, George Eliot. She was born Mary Ann Evans in 1819 in Warwickshire, England. Her novels include Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), and Silas Marner (1861). Middlemarch (1871), which charts women’s difficulties in ambition, love, commitment, and convention, is widely considered her masterpiece.

As an adolescent, Eliot participated in the conservative religious culture of her rural, farming family. When she moved to London as a young woman, she was exposed to new ways of thinking. In 1850, she began to edit and write for the radical intellectual publication Westminster Review. Surrounded by intellectuals who shucked the constraints of Victorian culture, Eliot met the married George Henry Lewes. The two moved in together, amid scandal, and remained controversially paired for 24 years until Lewes’s death.

Eliot was concerned that her early fiction, which dug into the grittier details of the lives of working people, would not be taken seriously. Novels by female authors were often dismissed as romantic drivel. She used the pen name George Eliot, and her first novel, Adam Bede, became wildly popular.

Success surprised Eliot, who suspected the work was too subversive to catch on. Here was a woman who lived outside convention and lacked prized feminine qualities of the era. In 1856, Eliot published an essay (anonymously) called “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.” Of the ideal female star, she wrote that “her nose and her morals are alike free from any tendency to irregularity,” and the reader can rest assured that the protagonist’s “sorrows are wept into embroidered pocket-handkerchiefs, that her fainting form reclines on the very best upholstery.” The rest of the essay is a not-so-subtle satire of the preferred female traits of the day, revealing Eliot’s awareness of how far she strayed from these norms.

If Eliot defied standards of conventional feminine beauty and behavior, she not did masquerade completely convincingly as a man. After reading her first collection of stories, Charles Dickens wrote to Eliot: “My Dear Sir: I have been so strongly affected by the first two tales in the book […] I hope you will excuse my writing to you to express my admiration of their extraordinary merit.” Dickens went on to admit that he strongly suspected George Eliot was not a man after all: “I have observed what seem to me to be such womanly touches, in those moving fictions, that the assurance on the title-page is insufficient to satisfy me, even now. If they originated with no woman, I believe that no man ever before had the art of making himself, mentally, so like a woman, since the world began.”

Eliot often made disparaging jokes about her appearance in letters to friends. Henry James described Eliot as “magnificently, awe-inspiringly ugly.” Another critic wrote of Eliot: “It must be a terrible sorrow to be young and unattractive: to look in the mirror and see a sallow unhealthy face, with a yellowish skin, straight nose, and mouse-colored hair.” And another critic who interviewed Eliot wrote that she was “a woman with next to no feminine beauty or charm.” Many of her biographers and interviewers have felt compelled to make similar remarks.

Eliot’s intellect and way with words, meanwhile, won her friends and lovers. After passing his initial judgment, Henry James said of his first meeting with Eliot, “Behold me, literally in love with this great horse-faced bluestocking!”

She seems to have lived more freed from the expectations of her society than hobbled by her refusal to accommodate them. After Lewes’ death, Eliot continued to set the rules for her own life. In her early 60, she married a friend 20 years younger. Her peers found this union even more shocking than her first.

Eliot’s novels have continued to sell for more than a century. In Middlemarch, she wrote, “And, of course men know best about everything, except what women know better.”

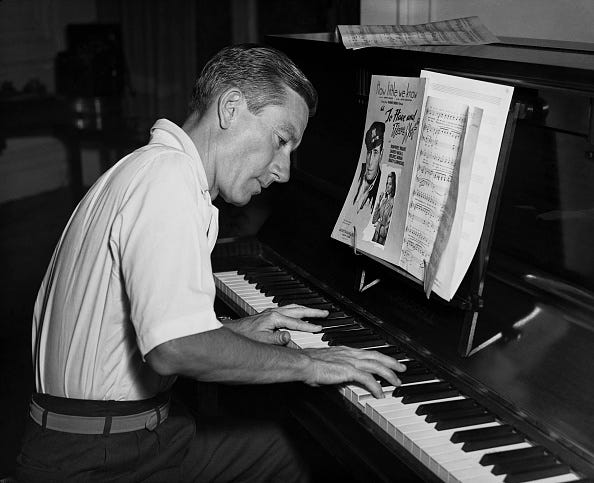

It’s the birthday of songwriter Hoagy Carmichael, born Hoagland Howard Carmichael in 1899 in Bloomington, Indiana. Hoagy got his nickname from a circus performer who once lived with his family. Carmichael’s parents were a horse-and-buggy driver and a piano player for silent film, and his mother got him started playing the piano when he was six years old. Carmichael joined the Army one day before the end of World War I, then came home to Bloomington to play piano for high school dances.

On visits to Chicago, Carmichael got acquainted with speakeasy jazz and was a fan of King Oliver and Louis Armstrong. The speakeasy scene set him up with a gig smuggling champagne, and he used the money to put himself through law school. Though his parents were supportive of his musical talents, Carmichael was eager to leave his poor roots, especially after his sister died from diphtheria — a “victim of poverty,” Carmichael said.

Law degree in hand, Carmichael barely got the chance to practice. He formed a band, began to write music, and by 1926 had penned his first hit, “Riverboat Shuffle.” After that, Hoagy dove into music full-time. His career took him to New York and eventually to Hollywood, where he wrote for soundtracks and appeared in many films.

His 1929 hit “Star Dust” quickly became a standard. By 1963, “Star Dust” had been recorded more than 500 times — the century’s most recorded song — and its lyrics had been translated into 40 languages. “Star Dust” was named by a friend, who said of the song: “That one’s all the girls, the university, the family, the old golden oak, all the good things gone, all wrapped up in a melody.”

Carmichael wrote “Star Dust” during a nostalgic visit to his alma mater, Indiana University, while recalling an old girlfriend. He said: “This melody was bigger than I. It didn’t seem a part of me. Maybe I hadn’t written it at all […] I wanted to shout back at it. ‘Maybe I didn’t write you, but I found you.’”

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

Demonstrate your support with our stylish new cap! Support poetry and The Writer's Almanac by wearing our new design which features the show's name prominently across the front of this 3 tone hat. Show name and logo are embroidered in white. We're an open book! One size fits most as it's adjustable. CLICK HERE to order.

So interesting! Thank you, Mr. Keillor.

It wasn't clear why Eliot's first marriage was a scandal.