The Writer's Almanac from Wednesday, September 27, 2017

“Flamingo Watching” by Kay Ryan from The Best of It. © Grove Press, 2010.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

The first steam-powered passenger railway began service in England on this date in 1825. It brought together the work of George Stephenson, builder of coal mine steam engines, and Edward Pease, who wanted to build a delivery system to bring coal to the market towns of Darlington and Stockton-on-Tees. Some Stockton businessmen advocated a canal system, but the other two towns on the line — Darlington and Yarm — both wanted a railway. Pease was planning to use horse-drawn coal wagons, however, until Stephenson informed him that a steam engine could pull a load 50 times greater than horses could manage. So a proposal for a railway line went before Parliament, and was thrown out twice. In 1821, supporters of the railway submitted a petition with 785 signatures, and the plan was finally approved. As an afterthought, the drafters of the official document added the permission to carry passengers on the train.

The train's inaugural journey went from Shildon to Stockton, with a top speed of 12 miles per hour. A man on horseback went before the train, carrying a banner that read Periculum privatum utilitas publica ("The private danger is the public good"). About 600 people were aboard, most of them riding in open coal cars. Dignitaries and rich backers rode in the sole passenger coach, which had been dubbed "The Experiment," and which had been built at a cost of 80 pounds sterling. George Stephenson rode on the footplate. A brass band boarded the train at Yarm to complete the journey, where the first steam-powered passenger train was greeted with a 21-gun salute and "God Save the Queen."

It's the birthday of writer Joyce Johnson, born Joyce Glassman in New York City (1935). She ran away to Greenwich Village when she was still a teenager, and got to know people at the center of the emerging Beat Generation. Her troubled, two-year affair with Jack Kerouac is recounted in her memoir, Minor Characters, A Young Woman's Coming of Age in the Beat Orbit of Jack Kerouac (1999), which won a National Book Critics Circle Award. She has also published Doors Wide Open: A Beat Love Affair in Letters 1957–1958, the letters she and Kerouac exchanged during their relationship.

Glassman said: "Artists are nourished more by each other than by fame or by the public. To give one's work to the world is an experience of peculiar emptiness. The work goes away from the artist into a void, like a message stuck into a bottle and flung into the sea."

It’s the birthday of Carrie Brownstein, born in Seattle in 1974. Brownstein co-founded the punk rock band Sleater-Kinney and co-developed the comedy show Portlandia.

Sleater-Kinney came to be in Olympia, Washington, in the mid-1990s. Time Magazine called the group “America’s best rock band,” while Rolling Stone hailed them as “America’s best punk band ever.” The group put out 10 albums and then went on hiatus in 2006, reuniting in 2015, the same year Brownstein published a best-selling memoir called Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl.

Now, Brownstein finds creative outlet in comedy. Her show Portlandia became wildly popular, charting 3.7 million viewers. Portlandia pokes fun at Pacific Northwest culture, depicting its subjects as both peevish and relaxed. In one episode, a couple sits down at a restaurant, only to abandon their table — and their dog tied up nearby — to appraise the farm that raised their chicken dinner. Meanwhile, the show chides a culture that is infamously laid-back. Brownstein said, “I live in a city where fleece is considered an appropriate fabric for any event.”

As a musician, comedian, actor, and author, Brownstein has made her career observing and commenting on culture. She credits her position as an outsider, “always existing on the periphery,” with her sharp and surprising vision. She said, “Starting from a place of normalcy or mainstream, you don’t get the same gumption or drive that you do from the fringes.”

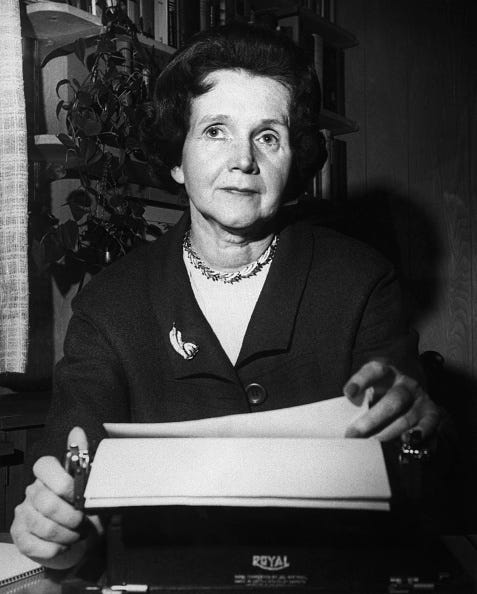

Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book Silent Spring was published on this date in 1962. Carson was a marine biologist, but she was also a crafter of lyrical prose who contributed to magazines like The New Yorker and Atlantic Monthly, and who had already published three popular lyrical books about the sea. One of these — The Sea Around Us (1951) — had won the National Book Award. In the course of her work, Carson became aware of the ways that chemical pesticides were harming plants and wildlife. She felt it was important to make the public aware of this, but she was not an investigative journalist and didn’t feel confident enough to write what she called the “poison book.” She began trying to interest magazines in the subject as early as 1945. In 1958, Carson’s friend mentioned that she was finding a lot of dead birds in her Massachusetts bird sanctuary. Carson, in turn, wrote to E.B. White, who was an editor at The New Yorker. She suggested that White write an article about pesticides. He said the magazine would be keen to publish such an article, but he encouraged her to write it herself. The article became a multiyear project that Carson pursued through personal tragedies like the death of her mother, and her own diagnosis with breast cancer in 1960.

By 1962, many scientists had published work that questioned whether the widespread and indiscriminate use of pesticides like DDT was safe. Carson gathered these reports in one place, and then used her literary talents to bring the issue to vivid life. The New Yorker serialized Silent Spring in the summer of 1962, and it was published in book form in September. The title comes from one of the book’s chapters, in which Carson paints a picture of a future spring morning without birdsong. “No witchcraft,” Carson writes, “no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves.”

The book was a huge best-seller, and although she was dreadfully ill from her cancer treatments, Carson appeared on many television shows to defend her research. Eric Sevareid, who interviewed Carson for CBS Reports, later said he was afraid she wouldn’t live long enough to see the broadcast of their interview. In June 1963, she appeared before a Senate subcommittee and gave policy recommendations that she had worked on for five years. She didn’t advocate a ban on all pesticides, but recommended that they be used more judiciously. Aerial spraying was the worst culprit, because it could end up on people’s private land without their knowledge or consent. “If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem,” Carson said.

Chemical companies, backed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, were not fans of the book. They tried to sue Carson, her publisher, and The New Yorker. They spent $250,000 on a smear campaign, calling her a “hysterical woman” and a communist, and casting doubt on her scientific bona fides. A former secretary of agriculture wondered publicly why a spinster with no children cared so much about genetics. But all the scandal only helped the book become a household name. President Kennedy read it with interest, and instructed his science advisors to look into Carson’s allegations against DDT. They determined that her claims held up, but it was still 10 years before the widespread use of DDT was banned in the United States. Carson still has her detractors today who say that the banning of DDT killed more people — due to malaria-carrying mosquitos — than Hitler.

Carson died of breast cancer in April 1964. She lived to see the book’s commercial success. She didn’t live to see the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, or the Environmental Protection Agency — all of which came about due, in large part, to Silent Spring.