TWA for Monday, February 27, 2012

"Pursuit" by Stephen Dobyns, from Cemetery Nights. © Penguin Books, 1987.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2012

Today is the birthday of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, born in Portland, Maine (1807). He entered Bowdoin College at the age of 15, and one of his classmates was Nathaniel Hawthorne; the two would remain lifelong friends. When Longfellow graduated, the college gave him a chair in modern languages, and he worked with translations for the rest of his life.

In 1831, he married Mary Potter, and they went on an extended tour of Europe. While they were in the Netherlands, Mary died from complications after a miscarriage. Longfellow was bereft and found solace in reading German poetry, and when he returned to America to teach at Harvard, he began writing poetry of his own. He wrote about uniquely American subjects, and he was the first American poet to be taken seriously abroad. His collection Ballads and Other Poems (1841) became wildly popular; it included his poems "The Wreck of the Hesperus" and "The Village Blacksmith." He wrote several popular narrative poems, including the book-length Evangeline (1847), The Song of Hiawatha (1855), and The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858). He also undertook the first American translation of Dante's Inferno (1867). He began the project to console himself after his second wife, Fanny, died when her dress caught fire in 1861.

It was on this date in 1860 that presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln gave a speech against slavery at Cooper Union in New York City. The popular pro-slavery argument of the day argued that Congress had no right to regulate slavery in new territories. The Dred Scott case of 1857 upheld that viewpoint, maintaining that the framers of the Constitution did not intend Congress to limit slavery. Lincoln believed that decision was wrong, and he spent months before the speech researching the positions of the 39 Founding Fathers on the issue of slavery.

That evening, the great hall was filled with 1,500 New Yorkers, curious to see this candidate, a lawyer who had very little formal education, a man whom they knew something of from his series of highly publicized debates with Douglas. One eyewitness remarked: "When Lincoln rose to speak, I was greatly disappointed. He was tall, tall, — oh, how tall! and so angular and awkward that I had, for an instant, a feeling of pity for so ungainly a man." Once Lincoln began to speak, however, "his face lighted up as with an inward fire; the whole man was transfigured. I forgot his clothes, his personal appearance, and his individual peculiarities. Presently, forgetting myself, I was on my feet like the rest, yelling like a wild Indian, cheering this wonderful man." Lincoln's law partner, William Herndon, was not present, but had read the speech beforehand; it was, he said, "constructed with a view to accuracy of statement, simplicity of language, and unity of thought. In some respects like a lawyer's brief, it was logical, temperate in tone, powerful — irresistibly driving conviction home to men's reasons and their souls."

The speech — one of his longest, and one of his least-quoted — was reprinted widely; The New York Times printed it in its entirety, on the front page, the next day. It made Lincoln famous, and he was invited to speak at engagements all over the country. That summer, the Republican Party named him their candidate for the 1860 presidential election.

He ended the speech with the words, "Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it."

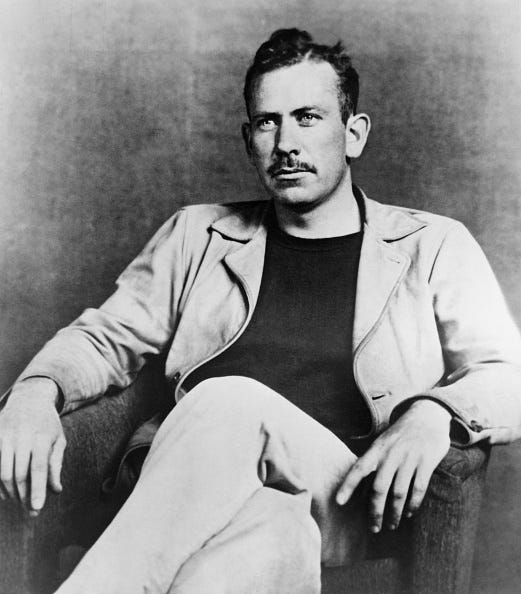

It's the birthday of John Steinbeck, born in Salinas, California (1902). His early books didn't sell well at all, and he supported himself as a manual laborer. His first success came with the 1935 novel Tortilla Flat, which was the story of King Arthur and the Round Table told through the lives of pleasure-loving Mexican Americans. He was paid several thousand dollars for the movie rights; the film was released in 1942 and starred Spencer Tracy and Hedy Lamarr. Steinbeck's book Of Mice and Men (1937) was very popular, but it was also considered vulgar and unpatriotic, and Steinbeck was accused of having an "anti-business attitude."

In the late 1930s, he was sent by a newspaper to report on the situation of migrant farmers, so he got an old bakery truck and drove around California's Central Valley. He found people starving, thousands of them crowded in miserable shelters, sick with typhus and the flu. He wrote everything down in his journal, and in less than six months, he had a 200,000-word manuscript. The Grapes of Wrath (1939) won the Pulitzer Prize, but the author was roundly condemned in some quarters for his anti-capitalist, pro-New Deal, pro-worker stance.

During World War II, Steinbeck wrote some government propaganda, and although he returned to social commentary in his post-war fiction, his books of the 1950s were more sentimental than his pre-war works. In the 1960s, he served as an advisor to Lyndon Johnson, whose Vietnam policies Steinbeck supported. Many accused him of betraying his leftist roots.

He said: "A writer out of loneliness is trying to communicate like a distant star sending signals. He isn't telling or teaching or ordering. Rather he seeks to establish a relationship of meaning, of feeling, of observing. We are lonesome animals. We spend all life trying to be less lonesome."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

CHECK OUT STEPHEN DOBYN’S POETRY COLLECTIONS