"The daisy follows soft the sun..." by Emily Dickinson. Public domain.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2011

It's the birthday of writer Jhumpa Lahiri, born in London (1967). Her parents were Bengali immigrants from India. When Lahiri was two years old, her father got a job as a librarian at the University of Rhode Island, and they moved to America. Her mother spent all day pushing young Jhumpa around in a stroller and making friends with everyone she saw on the street who looked Bengali. On weekends, the whole family would get together with other Bengali families, sometimes driving for hours to other states for a party. The adults cooked Bengali food and spoke Bengali and reminisced; the kids all watched television together.

Throughout her childhood, Lahiri wrote stories to entertain herself. She went to college at Barnard, then to graduate school at Boston University, where she earned what she called "an absurd number of degrees" — an M.F.A, a master's degree, and a Ph.D. She loved to write, but she struggled to get her stories published. She was on the verge of going to work in retail when Houghton Mifflin agreed to publish her first book for a small advance. That book was The Interpreter of Maladies, a collection of nine stories about Bengalis and Bengali-Americans living in suburban New England. The plots centered on the ordinary details of marriages, families, jobs, cooking, and hosting parties. The Interpreter of Maladies came out in 1999, but the publishers didn't expect to sell many copies so they only released it in trade paperback. As expected, it didn't get much notice at first.

Lahiri had no idea that The Interpreter of Maladies was a contender for any prizes, and then one day she got a phone call. She said: "I was in my apartment. We had just come back from a short trip to Boston and I was heating up some soup for my lunch. My suitcases were still not unpacked. And the phone rang. It was one or two in the afternoon. The person who called me was from Houghton Mifflin, my publisher, but no one I knew, and she said, 'I need to know what year you were born.' And then she asked some other fact like where I was born. I just told her. Sometimes people need some information for a reading, for a flyer or something. And then she said, 'You don't know why I am calling, do you?' And I said, 'No, why are you calling?' And she said, 'You just won the Pulitzer.'" It was the first time a paperback had ever won the Pulitzer. The Interpreter of Maladies became an immediate best-seller. Lahiri was uncomfortable with her new fame — she said, "If I stop to think about fans, or best-selling, or not best-selling, or good reviews, or not-good reviews, it just becomes too much. It's like staring at the mirror all day." So she doesn't read reviews, and she keeps her Pulitzer wrapped in bubble wrap.

Her next book was a novel, The Namesake (2003), another best-seller about Bengali-Americans; and her third book, a collection of stories called The Unaccustomed Earth (2008), debuted as No. 1 on the New York Times best-seller list.

Jhumpa Lahiri said about her writing: "I like it to be plain. It appeals to me more. There's form and there's function and I have never been a fan of just form. My husband and I always have this argument because we go shopping for furniture and he always looks at chairs that are spectacular and beautiful and unusual, and I never want to get a chair if it isn't comfortable. I don't want to sit around and have my language just be beautiful."

In her short story "The Third and Final Continent," from The Interpreter of Maladies, she wrote: "Whenever he is discouraged, I tell him that if I can survive on three continents, then there is no obstacle he cannot conquer. While the astronauts, heroes forever, spent mere hours on the moon, I have remained in this new world for nearly 30 years. I know that my achievement is quite ordinary. I am not the only man to seek his fortune far from home, and certainly I am not the first. Still, there are times I am bewildered by each mile I have traveled, each meal I have eaten, each person I have known, each room in which I have slept. As ordinary as it all appears, there are times when it is beyond my imagination."

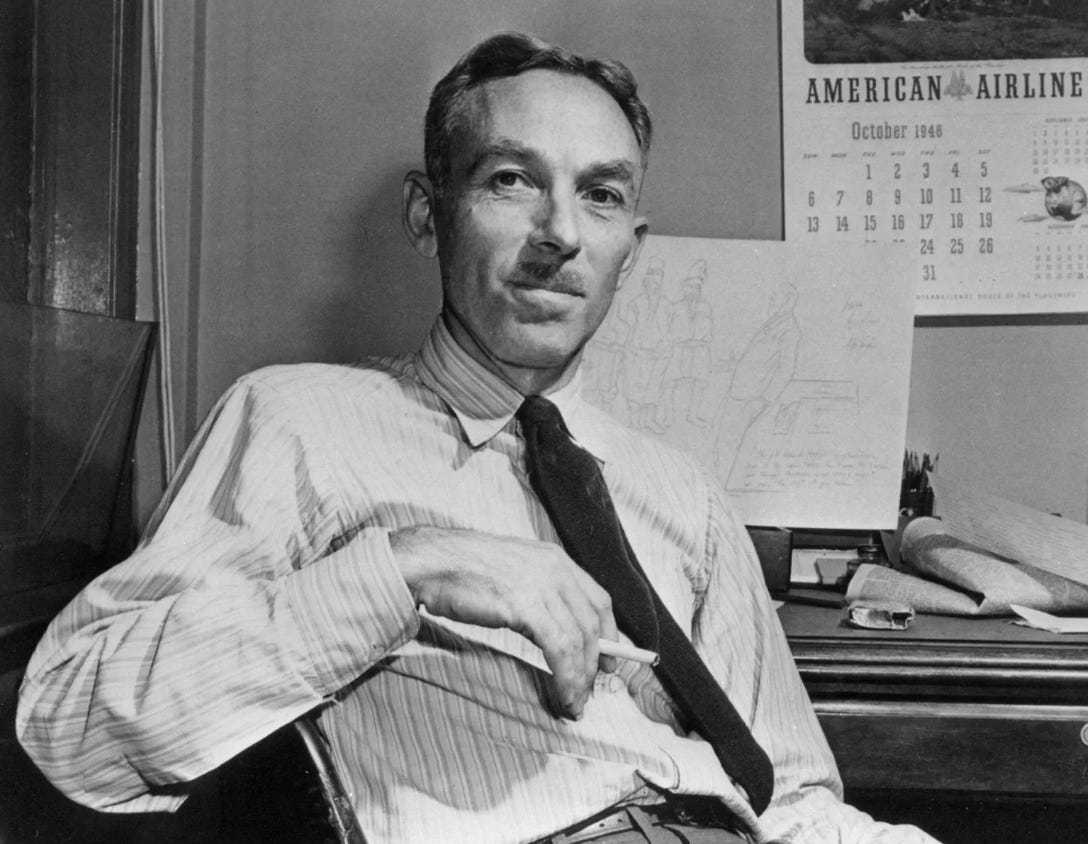

It's the birthday of the writer E.B. White, born Elwyn Brooks White in Mount Vernon, New York (1899). He started publishing essays when he was in his mid-20s. He said: "I had done a great deal of writing, but I lacked confidence in my ability to put it to good use. I went abroad one summer and on my return to New York found an accumulation of mail at my apartment. I took the letters, unopened, and went to a Childs restaurant on 14th Street, where I ordered dinner and began opening my mail. From one envelope, two or three checks dropped out, from The New Yorker. I suppose they totaled a little under a hundred dollars, but it looked like a fortune to me. I can still remember the feeling that 'this was it' — I was a pro at last. It was a good feeling and I enjoyed the meal."

After publishing some of his essays, The New Yorker decided to hire White as a staff writer, and he wrote for the magazine for nearly 60 years. In 1938, he and his wife — the New Yorker's fiction editor, Katharine Angell — left New York City and moved to a farm on the coast of Maine. There he continued to write essays, and his reflections on farming for Harper's were collected in the book One Man's Meat (1942).

White had 18 nieces and nephews who asked him to tell stories, so he started writing some down to make sure he wouldn't run out of ideas when one of them asked for a story. One day he fell asleep on a train and dreamed about a mouse-boy with human parents — White described him as "the only fictional figure ever to have honored and disturbed my sleep." Inspired by that character, he wrote Stuart Little, whichwas published in 1945. His next children's book, Charlotte's Web (1952), has sold more than 45 million copies. When it was published, Eudora Welty praised it in The New York Times, beginning her review: "E.B. White has written a book for children, which is nice for us older ones as it calls for big type. The book has liveliness and felicity, tenderness and unexpectedness, grace and humor and praise of life, and the good backbone of succinctness that only the most highly imaginative stories seem to grow."

White said: "Children are game for anything. I throw them hard words, and they backhand them over the net. They love words that give them a hard time, provided they are in a context that absorbs their attention. I'm lucky again: my own vocabulary is small, compared to most writers, and I tend to use the short words. So it's no problem for me to write for children. We have a lot in common."

In a letter to his brother, White wrote: "I discovered a long time ago that writing of the small things of the day, the trivial matters of the heart, the inconsequential but near things of this living, was the only kind of creative work which I could accomplish with any sincerity or grace. [...] The rewards of such endeavor are not that I have acquired an audience or a following, as you suggest (fame of any kind being a Pyrrhic victory), but that sometimes in writing of myself — which is the only subject anyone knows intimately — I have occasionally had the exquisite thrill of putting my finger on a little capsule of truth, and heard it give the faint squeak of mortality under my pressure, an antic sound."

It's the birthday of the literary critic and teacher Harold Bloom, born in New York City (1930). His parents were both Jewish immigrants, and his first language was Yiddish. He started reading English poetry before he'd ever heard the English language spoken aloud. He didn't do well in high school, but when he took the statewide Regents exams, he got the highest score in the state, and that won him a scholarship to Cornell University.

He went on to study literature at Yale in the 1950s, where the professors were prim and proper and all the students work jackets and ties to class. Bloom wore an old Russian leather coat and a pair of fisherman's trousers to class, and he became famous for his emotional attachment to poetry. He memorized everything he read, and could recite book-length poems both frontward and backward.

When he was 35, Bloom fell into a deep depression, and in the midst of that depression he had a terrible nightmare that a giant winged creature was pressing down on his chest. He woke up gasping for breath, and the next day he began writing a book that would become The Anxiety of Influence (1973), in which he argued that all great writers are obsessed with breaking away from the great writers of the past. The book made him famous, even though few people could understand it. A year after it was published, Bloom reread it himself, and found that he couldn't understand it either.

In the last few years, Bloom has been writing books for general readers because he thinks that scholars have forgotten how to read for pleasure. Many of his recent books have become best-sellers, including Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (1998) and How to Read and Why (2000).

Harold Bloom wrote, "Reading well is one of the great pleasures that solitude can afford you, because it is, at least in my experience, the most healing of pleasures."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

******************************************

To purchase That Time of Year: A Minnesota Life - Click HERE

“Keillor is very clearly a genius. His range and stamina alone are incredible—after 30 years, he rarely repeats himself—and he has the genuine wisdom of a Cosby or Mark Twain. He's consistently funny about Midwestern fatalism . . . and he's a masterful storyteller.”—Sam Anderson, Slate

Now that GK has "retired" I read thru his daily epistles, rather than listening to them in the background as I sift thru INBOX. So I'm retaining a LOT more of these chewable, golden nuggets!

Love your daily gems ❤️