“To Jane: The Keen Stars Were Twinkling” by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Public domain.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

On this date in 1789, the first Electoral College convened and elected George Washington as the first president of the United States. Only 10 states were represented in the college. Some had not held their presidential election yet, and others hadn’t yet ratified the Constitution and were therefore ineligible to vote. Congress finally certified the results on April 6, after a quorum was established. Each elector had two votes: all 69 electors present cast one of their votes for Washington. The second vote went toward determining who would be the vice president. John Adams was the runner up, with 34 votes. He provided balance to the ticket, too: he was from Massachusetts, and Washington was from Virginia, which was the largest state at that time.

Washington had led the Continental army to victory in the American Revolution, and he had served as the president of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, so he was an easy choice, and perhaps the only choice. But he really didn’t want the job. He wrote to a friend, “My movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to his place of execution: so unwilling am I, in the evening of a life nearly consumed in public cares, to quit a peaceful abode for an Ocean of difficulties …”

At his inauguration on April 30, Washington wore a simple suit of brown broadcloth. According to the journal of a senator who was present at his swearing in, Washington was very nervous: “This great man was agitated and embarrassed more than ever he was by the leveled cannon or musket.” Washington admitted as much in his inaugural address to Congress: “Among the vicissitudes incident to life, no event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order.”

The details of the office — and indeed, the entire system of American government — were still being hammered out when he took office. Throughout his presidency, Washington took great pains to distance himself from the monarchical customs and ceremonies of Britain. When the Senate asked him how he wanted to be addressed, and offered “His Highness” as an option, he turned them down in favor of the less lofty “Mr. President.” He didn’t wear a military uniform or any robes of state to official functions, appearing instead in a black velvet suit.

Washington served two terms and then stepped down in 1797, despite many calls for him to continue in office. He believed that it was crucial to set the precedent for a peaceful transition, and he longed for a quiet retirement at Mount Vernon, his Virginia plantation. He composed his 32-page farewell address with the help of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. In his speech, he urged the nation to think of itself as a unified body. He said that partisanship “serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passion.”

Washington only got to enjoy the quiet life at Mount Vernon for two years. He died of epiglottitis, a severe throat infection, in 1799.

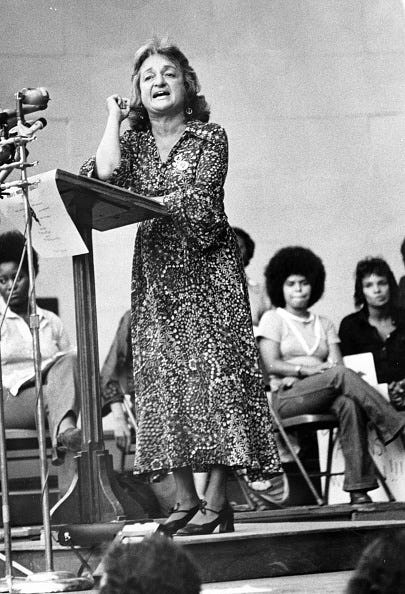

It’s the birthday of writer, activist, and feminist Betty Friedan (1921), who wrote the groundbreaking book The Feminine Mystique (1963), which explored the unhappy lives of American housewives and spurred the second wave of feminism in the United States during the 1960s.

She wrote: “The shores are strewn with the casualties of the feminine mystique. They did give up their own education to put their husbands through college, and then, maybe against their own wishes, ten or fifteen years later, they were left in the lurch by divorce. The strongest were able to cope more or less well, but it wasn’t that easy for a woman of forty-five or fifty to move ahead in a profession and make a new life for herself and her children or herself alone.”

On this day in 1938, a play debuted with the opening direction, “No curtains. No scenery. The audience, arriving, sees an empty stage of half-light.” It was Our Town by Thornton Wilder, first staged at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey, before shifting to Broadway. The play is by far Wilder’s most famous work — a story told in three acts about the fictional New Hampshire town of Grover’s Corners and its inhabitants at the start of the 20th century. Grover’s Corners was based on the real New Hampshire town of Peterborough, where Wilder had spent many summers. In an era of elaborate set design, Our Town was groundbreaking in its minimalism.

Today is the birthday of American aviator, inventor, and conservationist Charles Lindbergh (1902). In 1927, he became the first person to fly solo, nonstop, over the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to Paris. Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan, but grew up on a farm near Little Falls, Minnesota.

The University of Wisconsin didn’t interest him, so he left before graduating and enrolled in the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation’s Flying School in Lincoln, Nebraska. He became a barnstormer, which is a pilot who performs daredevil stunts at state and county fairs. He was working as an airmail pilot in 1926 when he heard about a $25,000 prize being offered to the first person who could fly from New York to Paris nonstop. He was only 25, and not very experienced, but he managed to gather some financiers in St. Louis and acquired a monoplane that he named “The Spirit of St. Louis.”

Charles Lindbergh took off from the dirt runway at Roosevelt Field, Long Island, on May 20, 1927, at 7:52 a.m., with a crowd of about 500 people watching. He packed four sandwiches, two canteens of water, and 451 gallons of gas. Thirty-three and a half hours and 3,500 miles later, he touched down in Paris at Le Bourget Field. Some 100,000 people rushed his plane. He was called a hero and nicknamed “The Lone Eagle” and “Lucky Lindy.” More than 4 million people lined the streets of New York City during a ticker-tape parade when he returned to America.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

Support THE WRITER’S ALMANAC

re: Lindberg>>Not to mention his strong embrace of fascism and bigotry is to miss a significant aspect of his life. (The personal torment of his child's kidnapping was, also, a major, protracted part of his life.)

In your brief comments acknowledging Charles Lindbergh’s birthday , I wish there could have been an additional comment about his bigoted views towards Jews and sympathy for the Nazi regime.