"Brown Penny" by William Butler Yeats. Public domain.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2011

It's the birthday of Gothic writer Horace Walpole, born in London (1717). Walpole's father was Britain's first and longest-running prime minister, and although he himself became a member of Parliament, Walpole avoided engaging in politics for the most part, preferring to spend his time writing thousands of letters to his friends and remodeling his "little play-thing-house." Through these two seemingly frivolous occupations, Walpole made his most lasting contributions.

It was in a letter to a friend that Walpole referenced a happy, accidental discovery, calling it "serendipity." The word was made up, created, he said, from the title of a fairy tale, "The Three Princes of Serendip." Serendip was the former name of Sri Lanka; in the story, Walpole explained, the princes "were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of." This particular letter and its serendipitous revelation were of no particular historical consequence. But Walpole's word slowly made its way into the lexicon.

It may not have, had Walpole not distinguished himself beyond letter writing. His other major literary achievement was the book The Castle of Otranto, which combined horror and romance in the first-ever Gothic novel, a genre that quickly became hugely popular.

But Walpole's obsession with Gothic wasn't limited to literature. Indeed, his book was inspired by his life's true focus: his house. It was named "Chopp'd Straw Hall" when he bought it, but Walpole quickly dubbed it the more romantic "Strawberry Hill" and set about expanding and decorating it in the classic medieval style. For 45 years he groomed his showpiece, creating a Gothic castle complete with an enormous oak front door, cloistered courtyard, and a huge stone-gray library. His renovations were so attention-getting that the home became a tourist destination, and Walpole opened it as a museum even while he still occupied it. Utterly unique at the time, like his novel, the home kicked off a whole architectural movement: Gothic Revival. In direct contrast to the austere neoclassical buildings popular at the time — including his own father's estate — Walpole's house slowly inspired the construction of other fanciful creations, buildings that looked ancient even when brand new. Like, for example, the Houses of Parliament. Walpole had done his best to shun the body politic, but the physical structure was rebuilt in the Gothic style after a massive fire destroyed most of it in 1834. Some might call it coincidence. Walpole would probably call it serendipity.

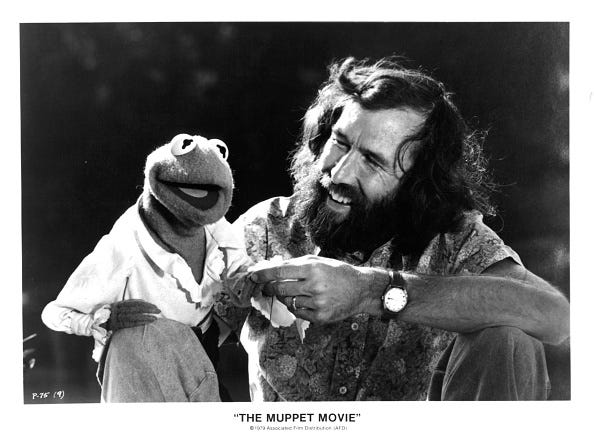

It's the birthday of Muppets creator Jim Henson, born James Maury Henson in Greenville, Mississippi (1936). Henson started his puppeteering career when he was in high school, performing for a children's show on a local TV station. In college, he majored in home ec so he could take craft and textile courses, and parlayed his early TV experience into his own five-minute show, which he produced daily with another college student. The show, called Sam and Friends, introduced him to two of the most important figures in his life: His collaborator became his wife, and one of his puppets, a turquoise lizard-like creature that Henson made from his mom's old coat and a dissected ping-pong ball became Kermit the Frog.

Henson continued making puppets, which he called Muppets, for commercials. As their popularity grew, they, and he, were asked to appear on a number of variety and talk shows like The Ed Sullivan Show. Finally, Henson was approached by a producer about adding some Muppets to the cast of a children's show in the works, to be called Sesame Street. Henson agreed, creating his famous characters Oscar the Grouch, Cookie Monster, Big Bird, and Bert and Ernie. Ernie, as well as Kermit, was performed by Henson himself.

Henson, though, had always imagined his Muppets could have an audience far broader than just little kids, and he booked them a gig on another new show, this one called Saturday Night Live. For the show's first season, the Muppets were billed before the other performers on the show's opening credits, but their segments were never successful. The SNL writers resented having to write for "felt," as one of them put it, and the Muppets weren't asked back for the second season. The parting was fortuitous, since meanwhile Henson had been developing his own show that, unable to find an American backer, had to be produced in England. The Muppets Show introduced characters like Miss Piggy, Fozzie Bear, and Gonzo, all of whom were soon starring in major feature-length films.

Henson, known as a "gentle giant" and the father of five children, continued to champion the idea that puppetry was an art form and could do far more than entertain children. Although his Muppets continued taking on new projects, Henson's new work became increasingly experimental and even edgy, like the Muppet-less films The Dark Crystal and cult classic Labyrinth.

When Henson died unexpectedly from undiagnosed pneumonia in 1990, thousands of mourners, who'd been instructed not to wear black, waved foam butterflies in the air during the nearly two-and-a-half-hour memorial service. Big Bird sang Kermit the Frog's famed song, "It's Not Easy Being Green," and dozens of performers gathered on stage for a medley of Muppet songs, which they sang in their characters' voices.

It's also the birthday of Steve Whitmire, born in an Atlanta suburb in 1959. Whitmire, a longtime Muppet performer, took over the role of Kermit the Frog upon Jim Henson's death. Serendipity.

Whitmire was 10 when Sesame Street premiered, and he became obsessed with the show, watching it twice a day, taping Muppets portions onto a cassette so he could lip sync along with puppets he built. His first was a Kermit, made from an aluminum potpie plate. He wrote a letter to Jim Henson, wondering if he'd written any books on puppet construction. Henson replied; he hadn't, but encouraged Whitmire to keep trying. He did, and several years later, performing in a puppet show at the local mall, Whitmire was approached by the organizer of an upcoming puppetry festival, which was going to be emceed by none other than Oscar the Grouch. She'd been shopping with her kids and happened to walk past — would Whitmire be interested in performing? Serendipity.

Whitmire, thrilled to meet a childhood idol of his, thought the festival was a dream come true. But when he got a call just a few months later from Oscar's puppeteer, suggesting Whitmire audition for Jim Henson, he realized he should dream bigger. Henson was in London, but it just so happened that his wife would be in Atlanta's airport on her way to oversee the construction of a Kermit float for Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade. Whitmire met her there, and when she asked him to perform for her, he pulled out a puppet he'd used on a local kid show. At the table behind them, some kids who'd seen the show perked up, recognizing his puppet, and came over to talk to him. Watching him interact with those kids, Jane Henson later told him, is what clinched it. At the age of 18, Whitmire moved to London to begin his career with the Muppets. Serendipity.

By order of the Act of September 22, 1789, the federal government officially established the United States Post Office and the office of the postmaster general, who was to report directly to the president. A network of 75 post offices already existed throughout the country — in fact, the position of postmaster general had been created years before, when Benjamin Franklin was appointed to the job by the Continental Congress. But the Act provided for the continuation and expansion of these services under the brand-new Constitution. The federal government would deliver the mail of American citizens — like, for instance, a letter from a young boy, born centuries later on the same day the Act was signed into law, sent to his hero, also born on the same day.

It's the birthday of poet Eavan Boland, born in Dublin in 1944. The author of the recent books Domestic Violence, New Collected Poems, and A Journey with Two Maps: Becoming a Woman Poet, Boland was only 18 when she published her first collection, despite feeling, she has often said, that there existed in Ireland "a magnetic distance between the word 'woman' and the word 'poet.'" Having overcome that atmosphere, having succeeded in putting her own life, the life of an Irish woman and mother, into her poetry, Boland says she is now honored to be called a "woman poet." A lucky thing, since she is often called the finest one in her native country.

She says: "I don't think poetry is a particularly good form of expression. Photographs are more accurate. Theatre is more eloquent. But poetry is a superb, powerful and true form of experience. I don't write a poem to express an experience. I write it to experience the experience. And the unforgettable poem I read, the one I remember, is the one that manages to convey the experience to me, which someone else once had — maybe hundreds of years ago — and, by a poise of music and language, convey it almost intact."

It's the birthday of F. Scott Fitzgerald, born Francis Scott Fitzgerald in St. Paul, Minnesota (1896). The son of a would-be furniture manufacturer who never quite made it big in business, Fitzgerald grew up feeling like a "poor boy in a rich town," in spite of his middle-class upbringing. This impression was only strengthened when he attended Princeton, paid for by an aunt, where he was enthralled by the leisure class, tried out and was cut from the football team, and fell in love with a beautiful young socialite who would marry a wealthy business associate of her father's. By the time Fitzgerald dropped out of college and entered the Army — wearing a Brooks Brothers-tailored uniform — it was little wonder he called the autobiographical novel he was writing The Romantic Egotist.

Fitzgerald's time at an officer training camp in Alabama didn't turn out as he'd hoped, either; the war ended before he ever made it to Europe, his book was rejected, and when he failed to make it big in New York City, his new debutante girlfriend, Zelda Sayre, called off their engagement.

Fitzgerald was probably much like most young men of his generation who dreamed of being a football star, the war hero, the wealthy big shot, the guy who gets the girl, but for a few things: he had talent, drive, and an unshakeable faith that he could translate all that familiar yearning into something new ... something that would get him, at least, the wealth and fame and the girl. His revised book, This Side of Paradise, got him all that and more when it was published. Requests for his writing came pouring in, Zelda married him, and the couple — a Midwesterner and a Southerner — became the quintessential New York couple, the epitome of the Jazz Age, a term Fitzgerald himself coined. And although they eventually died separated, she in a mental hospital, he in debt and obscurity, Fitzgerald's two greatest regrets remained, for the rest of his life, having failed to serve overseas and play Princeton football.

He said, "The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function."

And his daughter, "Scottie" Fitzgerald, said about her parents, "People who live entirely by the fertility of their imaginations are fascinating, brilliant and often charming, but they should be sat next to at dinner parties, not lived with."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

We have a Garage Sale Clearance collection in our store at garrisonkeillor.com

Would luv to read what u write about Fitzgerald more, since you've indubitably walked the same sidewalks and alleys in St. Paul.