“The New Song” by W.S. Merwin from Collected Poems: 1996-2011. © The Library of America, 2013.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2016

It was on this day in 1890 that federal troops killed almost 300 Lakota men, women, and children in the massacre at Wounded Knee. One of the survivors was Black Elk, the famous medicine man, who was 27 years old at the time of the massacre. He wrote: “… I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream. And I, to whom so great a vision was given in my youth, — you see me now a pitiful old man who has done nothing, for the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.”

It was on this day in 1916 that James Joyce published his first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

In James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, the novel’s hero, Stephen Dedalus, has come home from boarding school for the winter holidays and he is excited because for the first time in his life, he is sitting at the adult table for the Christmas dinner. The joy of the occasion diminishes, however, when an argument erupts over the Irish nationalist leader Charles Parnell and the role of politics in the Catholic Church. Stephen’s old nurse, Dante, proclaims that Parnell was a public sinner and not fit to lead a nation. Stephen’s father and his friend defend Parnell and insist that it was the Catholic Church’s betrayal of Parnell that caused Ireland’s lost chance for independence. Stephens’s mother pleads with exasperation, “For pity’s sake let us have no political discussion on this day of all days in the year.”

On this evening in 1940 during World War II, German forces began firebombing the city of London with such intensity that the fires that erupted became known as “The Second Great Fire of London.” Nearly one-third of the city was destroyed in mere hours, including 19 churches, 31 guildhalls, and all of Paternoster Row, the publishing center of London. Nearly 5 million books were destroyed. Some 1,500 fires were started by the high-explosive bombs; the timing of the air raid was carefully planned to coincide with low tide in the River Thames, which meant water was in short supply.

It was the 114th straight night of what was known as “The Blitz,” a systemic attack on London by Germany that began in September of 1940 and lasted until May of 1941. France, Belgium, Holland, and Norway had already fallen to Germany, and Adolf Hitler was determined to conquer Britain. The invasion was named “Operation Sea Lion,” but he underestimated the will of the British people, who had been stirred to determination by their new prime minister, Winston Churchill, who icily declared Britain would “never surrender.”

London schoolchildren practiced air raid drills by hiding beneath desks and pinning their hands over the backs of their necks. Wealthier citizens simply decamped to the countryside or bought steel “Anderson shelters,” which could be constructed in a backyard garden. The “Morrison shelter” was an iron cage that could double as an indoor table. Thousands of Britons with less money simply slept in the underground tube stations every night during the bombings.

The government didn’t like it, but they relented and brought in bunk beds and extra toilets. During the day, in the rubble, people on the street tacked up “Business as Usual” signs, joined the home guard, undertook fire-watching, and learned air raid precautions. Citizens were so resolute that journalist Edward R. Murrow, reporting from London, said, “Not once have I heard a man, woman, or child suggest that Britain should throw her hand.”

When the bombs began on December 29th, German observers on the French coast, nearly 100 miles away, watched as the night sky lit up. Both banks of the Thames were on fire. The fires stretched south from Islington to the edge of the St. Paul’s Cathedral churchyard, an area far greater than the first Great London fire of 1666. Winston Churchill ordered all available men to fight the fires outside St. Paul’s Cathedral in an effort to save the structure, which had been built by architect Christopher Wren after the previous cathedral had been destroyed in the 1666 fire. Wren was buried in the Cathedral.

A photographer named Herbert Mason was on top of the offices of the Daily Mail newspaper on Fleet Street when he took a picture of the cathedral with smoke and fire rising all around her. The photo became a symbol of Britain’s steadfast strength. The photo was called “War’s Greatest Picture.”

The Blitz lasted until May of 1941, when Hitler, who had vastly underestimated the resilience of Britain’s Royal Navy Air Force, turned his attention to the Soviet Union.

Britain never surrendered. In June of 1940, when he accepted the position of prime minister, Winston Churchill had declared: “Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be free, and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands; but if we fail, then the whole world will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say: ‘This was their finest hour.’”

In the rubble of the Second Great Fire was discovered a Gothic doorway, a seventh-century arch, a Roman wall, and various Roman relics.

In 1944, the bells of St. Paul’s Cathedral rang out to celebrate the liberation of Paris.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

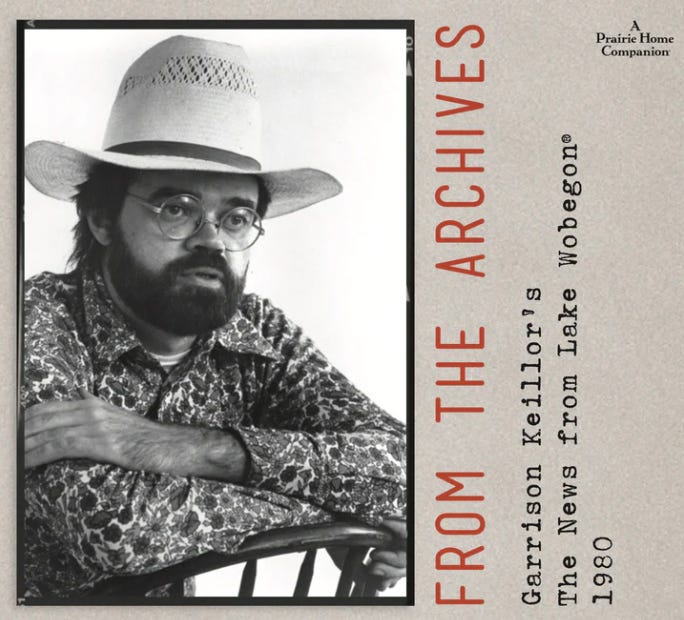

From the Archives: Garrison Keillor’s The News from Lake Wobegon - 1980 (3 CDs)

CLICK Link

Thank you for reminding us what courage looks like and how history repeats and repeats itself. And thank you for reminding us that if we live in America we live on blood-soaked soil.

Thanks for the great stories, enjoy reading TWA.