TWA for Thursday, February 23, 2017

“Lucky” by Kirsten Dierking from Northern Oracle. © Spout Press, 2007.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

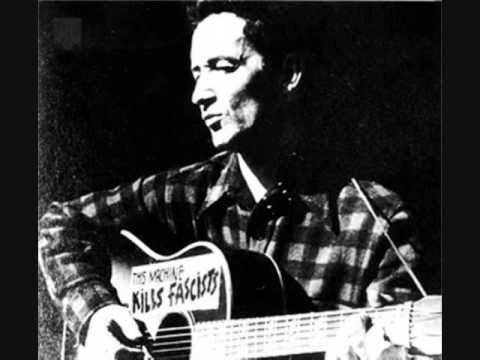

It was on this day in 1940 that American folk singer and activist Woody Guthrie wrote the lyrics to “This Land is Your Land.” Guthrie was sitting in his room at Hanover House, a transient hotel in New York City, when he became tired of listening to Kate Smith sing Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” on the radio. Guthrie had left home at 15 to travel the country by freight train, earning a living mostly as a painter-for-hire, but he also had his guitar and harmonica, and he became quite well known in the hobo camps and migrant farms for his songs from rural Oklahoma, where he’d grown up. He’d been all across the country by the time he hit New York and the Hanover Hotel, and he didn’t think America, or at least the poor, hardworking one he’d seen on his travels, felt very blessed, at all.

The first mass inoculation of the Salk vaccine against polio began on this date in 1954, at the Arsenal Elementary School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The year before, there had been 35,000 reported cases of the highly contagious disease — and by 1962, after the vaccine came into general usage, there were 161.

It’s the birthday of Baroque composer George Frideric Handel (1685), born in Halle, Germany. Handel went to London in 1710, which had lively and lucrative opportunities for a composer. Once there, he composed the opera Rinaldo in two weeks and wrote and performed for English royalty like Queen Anne, who provided him with a generous salary. Soon enough, he was made Master of the Orchestra at the Royal Academy of Music, the first Italian opera company in London. He became a British citizen shortly thereafter (1726). He once said, “What the English like is something they can beat time to, something that hits them straight on the drum of the ear.”

When King George I requested a concert on the River Thames, Handel responded by composing his famous Water Music. In July of 1717, King George boarded a barge on the river; another barge carrying around 50 musicians began traveling up the Thames; and Londoners also took to the water in boats and barges to hear the music. The king was so happy he asked for the concert to be repeated three times, up and down the River Thames.

Handel turned to composing oratorios when it became clear that the enthusiasm for Italian opera was waning. During Lent of 1735 alone, he produced 14 concerts, most of them oratorios. He also suffered anxiety and depression, and a stroke had impaired the movement of his right hand, but he didn’t stop composing, even after he lost sight in his right eye, and then the left. He composed Messiah in 24 days. When he was done, he wrote “Soli Deo Gloria,”: “To God alone the glory.” Handel was so popular that when his Music for Royal Fireworks debuted, more than 12,000 people came to hear it (1749).

George Frideric Handel died in his bed in 1759. He had no wife, and no children, and left most of his money to his servants and charities. He had lived in the same rented house at 25 Brook Street, in the Mayfair District of London, for many years. It’s now the Handel House Museum. More than 3,000 people attended his funeral.

About Handel, Beethoven said, “Go to him to learn how to achieve great effects, by such simple means.”

Today is the birthday of the English diarist Samuel Pepys, born in London (1633). His background was humble: his father was a tailor, and his mother came from a family of butchers. Pepys was the fifth of eleven children; his older siblings died one by one, and he ended up being the eldest surviving child. He went to St. Paul’s School in London, and later entered Magdalene College at Cambridge on a scholarship. Not much is known about his university days except that he did get in trouble once for being “scandalously overserved with drink.”

When he was 22, he married Elizabeth Marchant de Saint-Michel, the beautiful 15-year-old daughter of a penniless French refugee. He went to work doing odd jobs for his cousin, Admiral Edward Montagu. The young couple lived in a tiny room, and Pepys later recalled how his wife stoked the coal fires and washed his “foul clothes … with her own hand for me, poor wretch! … for which I ought forever to love and admire her, and do.” In 1658, Pepys had a bladder stone surgically removed — a painful and dangerous operation at that time, carried out without anesthetic or antiseptic — and celebrated the anniversary of the successful surgery for many years. Through his cousin’s connections, Pepys was given a position as clerk of the acts of the navy, which came with a nice annual salary and an official residence. At first, he knew nothing about the navy, and just enjoyed the status and good company that came with his job. After a while, though, this began to bother him, and he began to study and learn all he could about every aspect of the navy.

Pepys began keeping his famous diary on January 1, 1660, as the result of a New Year’s resolution. His first entry begins: “This morning (we living lately in the garret,) I rose, put on my suit with great skirts. Went to Mr. Gunning’s chapel at Exeter House, where he made a very good sermon. … Dined at home in the garret, where my wife dressed the remains of a turkey, and in the doing of it she burned her hand.” Pepys wrote about the plague of 1665, the Great Fire of 1666, and the coronation of Charles II. He also shared gossip and wrote about his health, diet, toilet habits, and a number of love affairs. He wrote in a kind of shorthand, and, if his subject matter was particularly scandalous, he substituted foreign and code words for some of the English ones. He gave up the diary in 1669, fearing that it was the reason for his failing eyesight. His last entry, dated May 31, reflects his regret: “And so I betake myself to that course which is almost as much as to see myself go into my grave — for which, and all the discomforts that will accompany my being blind, the good God prepare me.”

It’s the birthday of suspense novelist John Camp (1944), also known by his pen name John Sandford, born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He started out as a crime reporter for the Miami Herald and then moved to the St. Paul Pioneer Press in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he won a Pulitzer for a series of articles about a family farm during the American farming crisis. His novels often feature Minnesota police detectives with something to prove and unexpected elements to the common “thriller” formula. His book Deadline embraces the idea of a “slow-speed chase” across the Mississippi in paddleboats, and another time in golf carts. He says the trick to keeping his books fresh is mostly a matter of “thinking up good villains.”

Most of his books are set in Minneapolis and St. Paul, and he believes Minnesota breeds a particular kind of criminal. He once said: “When people kill up here, it’s not the chaotic street crime [they have] in Miami. We have these elaborate, cold-blooded murders that incubate in the winters. My first week in St. Paul, some guy killed his wife and fed her body down the garbage disposal. That’s Minnesotan.”

His next novel, Golden Prey (2017), will come out this April.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

The Writer’s Almanac Paperweight