TWA for Thursday, March 9, 2017

“Field Guide” by Tony Hoagland from Unincorporated Persons in the Late Honda Dynasty. © Graywolf Press, 2010.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

On this date in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Emergency Banking Relief Act, kicking off 100 days of New Deal legislation.

Roosevelt had only been in office for five days. The country was in the grip of the Great Depression, and the banking system was on the verge of collapse as people rushed to withdraw their savings. Banks were closed in all 48 states. As soon as he took office, FDR called Congress into a special session that would last for three months. He declared a four-day “bank holiday” that shut down all banks and even the Federal Reserve while Congress worked on legislation. The Emergency Banking Act was introduced in the House first, and representatives were in such a hurry to pass it that they didn’t wait for their own individual copies, but rather listened as the single copy was read aloud, and voted on it immediately. In Roosevelt’s first radio Fireside Chat on March 12, 1933, he said: “The new law allows the 12 Federal Reserve Banks to issue additional currency on good assets and thus the banks that reopen will be able to meet every legitimate call. The new currency is being sent out by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to every part of the country.” The government hoped that these assurances would be enough to lure people — and their money — back to the beleaguered banks.

When the banks began opening up again the next morning, people lined up to bring their money back, and by the end of March, about two-thirds of the money that had been taken out of the nation’s banks had been redeposited. Wall Street took note and the stock market began to rebound. The Emergency Banking Act was designed to be only a temporary measure; later that year, Congress passed the 1933 Banking Act, which established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or FDIC, which still guarantees deposits against bank failure.

It was on this day in 1796 that Napoleon Bonaparte, the future emperor of France, married Josephine de Beauharnais, an older widow with two children. The marriage scandalized Bonaparte’s family, but he was undeterred in his passion. He called Josephine, “worse than beautiful.” He once wrote to her, “I awake full of you. Your image and the memory of last night’s intoxicating pleasures has left no rest to my senses.” Josephine’s given name was Marie Josephe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie and she was known as “Rose.” Napoleon Bonaparte, however, preferred “Josephine,” and that’s how she was known from the moment they met.

Napoleon was two hours late to the wedding. They’d been engaged for just two official weeks before marrying. In the marriage contract, she made herself four years younger and he added 18 months to his age to make himself 26. He was scruffy, skinny, unkempt, jealous, and once declared, “Power is my mistress.” Josephine was described as sexy, with a low voice and a “lionine walk.” On their wedding day, he gave her a gold medallion with the inscription, “To Destiny.” Two days after the wedding ceremony, Bonaparte left to lead the French army in Italy.

Later, they both committed infidelity, and when it became clear Josephine could not provide him with an heir, they divorced. They were still so besotted that they read statements of devotion to one another at the divorce ceremony.

Of his new wife, he simply said, “I married a womb.”

It’s the birthday of English poet, novelist, and gardener Vita Sackville-West, in Kent, England (1892). Sackville-West had a decade-long affair with fellow writer Virginia Woolf. Woolf used her as the inspiration for the androgynous title character of her famous novel Orlando: A Biography (1928). Sackville-West’s son Nigel once referred to the novel as “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature.”

She spent her childhood in the enormous Knole House, which was designed as a “calendar house”: it had 365 rooms, 52 staircases, 12 entrances, and seven courtyards.

It’s the birthday of technology writer David Pogue, born in Shaker Heights, Ohio, in 1963, one of the best-selling “how-to-guide” authors ever. He’s written several books in the For Dummies series, including the first guide to Mac computers and guides to opera and classical music and magic. His novel Hard Drive was a New York Times “notable book of the year.” Though he’s best known for his commentary on technology, he is also a music and theater geek who spent 10 years conducting and arranging Broadway musicals in New York. Demand for composers was slightly less urgent than demand for computer experts, however, and he made his first foray into technology by teaching Broadway folks like Stephen Sondheim how to use their Macs. In between his numerous regular print and television appearances, he finds time to write song spoofs, cartoons, and various animations, which he publishes on his website. He has also hosted a NOVA miniseries on PBS called Making Stuff, which explored the materials that will shape our future.

It’s the birthday of a writer who called his books “the chewing gum of American literature.” That’s crime novelist Mickey Spillane, born Frank Morrison Spillane in Brooklyn (1918). His Irish father was a bartender, and Spillane grew up in a tough neighborhood in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He worked odd jobs, including as a lifeguard, circus performer, and salesman. He was selling ties at a department store when he met a coworker whose brother produced comic books, and he was convinced to try writing some himself. Spillane worked writing comic prose for a year, then left to join up with the Army Air Forces after Pearl Harbor. After the war, he returned to comics. He said, “I wanted to get away from the flying heroes and I had the prototype cop,” so he invented a private eye hero named Mike Danger. Danger was a flop, so Spillane renamed him Mike Hammer and wrote a novel instead.

I, the Jury (1947) took him just three weeks to write, and it was an instant hit. He turned out more than 30 novels, most of them featuring Mike Hammer, including Kiss Me, Deadly (1952), The Girl Hunters (1962), Body Lovers (1967), and The Killing Man (1989). His novels were incredibly violent, usually ending with Hammer executing people. The critics panned Spillane, but he didn’t care. He said, “Those big-shot writers could never dig the fact that there are more salted peanuts consumed than caviar.” He said he never had a character who drank cognac or had a mustache, because he didn’t know how to spell those words. He said: “I have no fans. You know what I got? Customers. And customers are your friends.” Spillane was incredibly popular — his books have sold more than 225 million copies.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

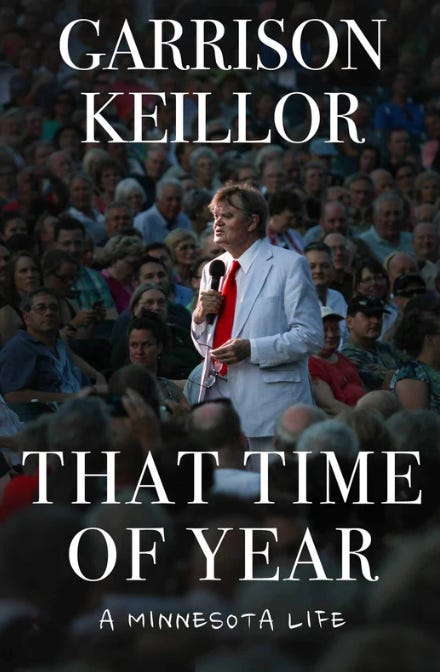

RELEASE WEEK - March 7th That Time of Year: A Minnesota Life (slightly revised) Softcover