“Modern Declaration” by Edna St. Vincent Millay from Selected Poems. © Yale University Press, 2016.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

Today is the birthday of Scottish writer Muriel Spark, born in Edinburgh (1918). She is best known for her coming-of-age novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), about a strong-willed teacher who selects six of her grade-school students to mentor into the “crème de la crème” of the Marcia Blaine School for Girls. Spark almost certainly drew inspiration for the plot from her own days at a public all-girls school in Edinburgh, where she was a talented student from a young age. The book was selected by Time Magazine as one of the hundred best English-language novels since 1923; it was also made into a film starring Maggie Smith in 1969, for which Smith won the Academy Award.

It is the birthday of the man who once said, “To me, poetry is somebody standing up, so to speak, and saying, with as little concealment as possible, what it is for him or her to be on earth at this moment.” That is the contemporary poet Galway Kinnell, born in 1927 in Providence, Rhode Island.

Kinnell graduated with a BA from Princeton University in 1948, where he was the classmate of fellow future poet W.S. Merwin. He spent many years studying abroad through the 1960s before returning to the U.S. to join the Congress for Racial Equity, helping to register black voters in the segregated South; his civil rights work at one point found him jailed alongside a pimp and a car thief. Still, Kinnell remained an active opponent of oppression, war, and environmental misconduct.

It’s the birthday of a man who loved words and who said he had a “lifetime devotion to puns,” humorist S.J. Perelman, born in Brooklyn (1904), whom The New York Times Magazine once called “the funniest man alive.”

He wrote sentences like, “[The waiters’] eyes sparkled and their pencils flew as she proceeded to eviscerate my wallet — pâté, Whitstable oysters, a sole, and a favorite salad of the Nizam of Hyderabad made of shredded five-pound notes.”

For decades, Perelman wrote for The New Yorker magazine, mostly short humorous sketches, which he described as “feuilletons.” It’s a French word that means “leaves of a book.” Perelman said that he was preoccupied “with clichés, baroque language, and the elegant variation.” He said he was influenced by James Joyce and by another Irish writer, Flann O’Brien, and he was a big fan of P.G. Wodehouse.

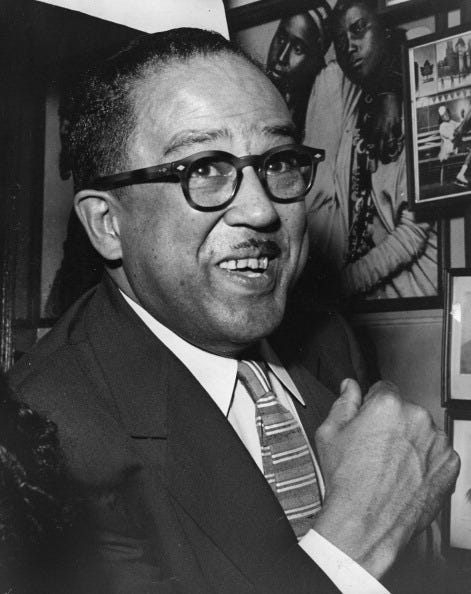

Today is the birthday of the man known as “The O. Henry of Harlem,” American poet Langston Hughes (1902). In 1926, he was working as a busboy at a hotel in New York City when the poet Vachel Lindsay arrived for dinner. Hughes placed some poems under Lindsay’s dinner plate. Intrigued, Lindsay read them and asked who wrote them. Hughes stepped forward and said, “I did.” And that’s how he came to publish his first volume of poetry, The Weary Blues (1926), at the age of 24.

He was born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri. His mother was a schoolteacher and his father a storekeeper. His father left the family and moved to Mexico, leaving Hughes mostly in the care of his grandmother, Mary. She was one of the first women to attend Oberlin College, and read to Hughes all the time. By the time he was 12 years old, he’d lived in six different cities. He said: “I was unhappy for a long time, and very lonesome, living with my grandmother. Then it was that books began to happen to me, and I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books — where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas.”

He went to college for a little while, but quit because of racism. He mostly traveled, working as a doorman at a nightclub in Paris, a seaman on ships, a waiter, and a truck farmer. He went to the Canary Islands, Holland, France, and Italy, writing poems and essays about the African-American experience.

Langston Hughes became a prominent member of the Harlem Renaissance, a group of African-American artists and writers in Harlem, New York, that included Zora Neale Hurston and Countee Cullen. Langston Hughes’s books include Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), Not Without Laughter (1929), and The Ways of White Folks (1934). He was a prolific letter writer, sometimes composing as many as 30 or 40 a night. He had so many in his sock drawer, he had to find another drawer for his socks. At the end of his life, he had enough letters to fill 20 volumes of books.

Langston Hughes’s ashes are interred beneath the entrance to the Arthur Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. The inscription above his ashes is from his poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers. It says, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

When asked what he wrote about, Langston Hughes answered, “Workers, roustabouts, and singers, and job hunters on Lenox Avenue in New York, or Seventh Street in Washington or South State in Chicago — people up today and down tomorrow, working this week and fired the next, beaten and baffled, but determined not to be wholly beaten, buying furniture on the installment plan, filling the house with roomers to help pay the rent, hoping to get a new suit for Easter — and pawning that suit before the Fourth of July.”

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

Do you know an English Major that deserves this shirt?

I miss listening to Garrison in his daily letters. What happened to them?

With deep feelings of gratitude for daily TWA, source of otherwise remote information thoughts, referrals for online and library searches; for goodwill, humor, optimism, faith, and connection. Carolyn Anderson, Silver Lake NY.