“To Sara, 1999” by Bill Jones from At Sunset, Facing East. © Apprentice House, 2016.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

It’s the birthday of the physician and lexicographer Peter Mark Roget, born in London, England (1779). He was a working doctor for most of his life, but he was also a Renaissance man, a member of various scientific, literary, and philosophical societies. In his spare time, he invented a slide rule for performing difficult mathematical calculations, and a method of water filtration that is still in use today. He wrote papers on a variety of topics, including the kaleidoscope and Dante, and he was one of the contributors to the early Encylopaedia Britannica.

He was 61 years old, and had just retired from his medical practice, when he decided to devote his retirement to publishing a system of classifying words into groups based on their meanings. Other scholars had published books of synonyms before, but Roget wanted to assemble something more comprehensive. He said, “[The book will be] a collection of the words it contains and of the idiomatic combinations peculiar to it, arranged, not in alphabetical order as they are in a Dictionary, but according to the ideas which they express.”

He organized all the words into six categories: Abstract Relations, Space, Matter, Intellect, Volition, Sentient and Moral Powers. And within each category, there were many subcategories. The project took him more than 10 years, but he finally published his Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases in 1852. He chose the word “thesaurus” because it means “treasury” in Greek.

Roget’s Thesaurus might have been considered an intellectual curiosity, except that at the last minute Roget decided to include an index. That index, which helped readers find synonyms, made the book into one of the most popular reference books of all time. It is considered one of the great lexicographical achievements in the history of the English language, and it has been helping English students pad their vocabularies for more than 150 years.

It’s the birthday of Joseph Farwell Glidden, born in Charleston, New Hampshire (1813). For centuries hedgerows and stone walls were the only way to keep livestock contained; in the American West, cowboys followed herds of cattle to make sure no harm came to them. Glidden saw an exhibition in which a wooden rail with nails protruding from it kept livestock at a distance. He rigged up an old coffee grinder to twist strands of wire around each other, then clipped off the protruding ends to make barbs. A number of men filed patents for similar barbed fences at the same time, and there was a tremendous fight, but Glidden won, and his barbed wire factory made him one of the country’s richest men. That was the end of the Wild West. Long cattle drives came to an end, and longhorn cattle began to disappear; it wasn’t necessary to breed cattle tough enough to survive out on the range anymore.

It’s the birthday of the man who created the most famous fictional teddy bear in the world: A.A. Milne, the father of Winnie-the-Pooh, was born today in London (1882). A young H.G. Wells was once his schoolteacher and Milne went to Trinity College on a mathematics scholarship, but his passion was writing, particularly light verse and plays. Milne was a lifelong pacifist, though he served in World War I, enlisting in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and then working in the Royal Corps of Signals. Milne was also an atheist, and he once said: “The Old Testament is responsible for more atheism, agnosticism, disbelief — call it what you will — than any book ever written. It has emptied more churches than all the counter-attractions of cinema, motor bicycle, and golf courses.”

He wrote for the British humor magazine Punch for a number of years, played cricket on the same team as Arthur Conan Doyle and J.M. Barrie — called “The Allahakbarries” — and penned several plays, like Mr. Pim Passes By (1921) and Toad of Toad Hall (1929) before the pudgy bear took over his life and became a worldwide sensation.

Milne was on holiday with his son, Christopher Robin, whom the family called “Billy,” when he began playing around with poems about the stuffed animals in his son’s nursery, particularly a teddy bear his son called “Edward the Bear.” The world of Hundred Acre Wood, which Milne based on Ashdawn Forest in East Sussex, England, was quickly populated with a gloomy donkey named Eeyore, an excitable entity named Tigger, a piglet named Piglet, and a fussy owl named Owl. They were shepherded by a little boy with a bowl-haircut who carried Milne’s son’s name, Christopher Robin. Winnie-the-Pooh was first featured in a Christmas story, “The Wrong Side of Bees,” published in the London Evening News in December of 1925. By 1931, Winnie-the-Pooh was a million-dollar business and an American magazine had named Milne’s son the most famous 11-year-old in the world.

Milne wasn’t altogether happy that the “bear of very little brain” had overshadowed what he considered his more serious writing. He said: “It seems to me now that if I write anything less realistic, less straightforward than ‘The cat sat on the mat,’ I am ‘indulging in a whimsy.’ Indeed, if I did say that the cat sat on the mat (as well it might), I should be accused of being whimsical about cats; not a real cat, but just a little make-believe pussy, such as the author of Winnie-the-Pooh invents so charmingly for our delectation.”

Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928) are now considered classics of children’s literature.

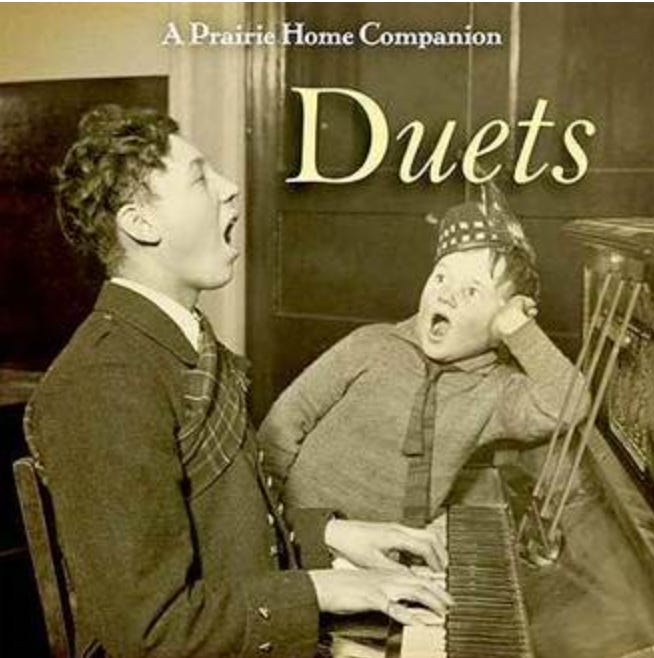

It’s the birthday of Oliver Hardy, born Norvell Hardy in Harlem, Georgia (1892). He studied law and sang professionally before he met Stan Laurel; they were one of the few teams to move smoothly from the vaudeville hall to full-length film comedies. They were most famous during the ’30s, and they won an Oscar for a short film called The Music Box, in which they attempted to get a piano up a steep staircase. The staircase wasn’t on a back lot; it was a real staircase that still stands in a residential neighborhood in Los Angeles. Ray Bradbury wrote a short story about a couple of Laurel and Hardy fans who fell in love there, and who signaled each other by leaving bottles of champagne on the steps.

You forgot to mention the Canadian connection re the name of the bear coming from the city of Winnipeg and how the bear got to the London Zoo via a Canadian Soldier who brought it with him as a mascot during World War I