TWA for Wednesday, September 7, 2011

"Police Notes" by Alice N. Persons, from Don't Be a Stranger. © Sheltering Pines Press, 2007.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2011

It's the birthday of Modernist poet Edith Sitwell, born in Scarborough, England (1887). Her parents, Sir George and Lady Ida Sitwell, were baffled by their daughter. While Lady Ida was a beauty, Edith was not. She was extremely tall and thin, with a curved spine and a hooked nose. Her parents forced her to wear an iron brace on her back and a contraption on her nose in an attempt to make her more conventionally attractive. Edith was a bright and curious child, but her father decided that formal education made women less womanly, so he refused to let her go to school. When she was a teenager and it came time for her to make her debut in society, she engaged a man in a debate over his classical music preferences, and her parents were horrified and pulled her back out of social gatherings. She left her family on such bad terms that she didn't even attend her mother's funeral.

Instead, she made her own life as a Modernist poet and a notable public personality. She published many books of poems, including Rustic Elegies (1927), The Song of the Cold (1948), Gardeners and Astronomers (1953), and The Outcasts (1962). Her poetry has generally been overshadowed by her colorful personality. To accentuate her dramatic features, she wore enormous rings, turbans, and old-fashioned gowns. She said, "I can't wear fashionable clothes. If I walked round in coats and skirts, people would doubt the existence of the Almighty." She befriended T.S. Eliot and Graham Greene, and later in her life, championed Dylan Thomas. She considered Marilyn Monroe a soulmate, and the two women read poetry aloud together.

Sitwell's best-known work is Façade, a series of poems that she set to music — each poem was meant to be read in a specific rhythm. The composer William Walton wrote the music and conducted a live orchestra during the performance. All the audience could see was a curtain painted like a huge face, with a hole in the center for a mouth. Sitwell sat behind the hole, reciting her words through a megaphone. Apparently the first London performance of Façade went so badly that an old woman in the audience waited outside the curtain afterward to hit Sitwell with an umbrella; Noel Coward walked out; and even Virginia Woolf didn't understand the poetry. Woolf wrote: "So I judged yesterday in the Aeolian Hall, listening, in a dazed way, to Edith Sitwell vociferating through the megaphone. [...] I should be describing Edith Sitwell's poems, but I kept saying to myself 'I don't really understand ... I don't really admire.' The only view, presentable view that I framed, was to the effect that she was monotonous. She has one tune only on her merry go round." When Sitwell performed Façade in New York more than 20 years later, it was extremely popular.

Sitwell said: "I am not an eccentric. It's just that I am more alive than most people. I am an unpopular electric eel in a pool of catfish."

And, "It is as unseeing to ask what is the use of poetry as it would be to ask what is the use of religion."

It's the birthday of critic and novelist Malcolm Bradbury, born in Sheffield, England (1932). His father worked for the railways and wanted his son to drop out of school and get a job when he was 15, but Malcolm convinced him that it was worth staying in school for a couple of years to see if he could get a university scholarship. He did, and he went on to become a famous academic and novelist who satirized university life in novels like Eating People is Wrong (1959), Stepping Westward (1965), and The History Man (1975).

The History Man begins: "Now it is the autumn again; the people are all coming back. The recess of summer is over, when holidays are taken, newspapers shrink, history itself seems momentarily to falter and stop. But the papers are thickening and filling again; things seem to be happening; back from Corfu and Sete, Positano and Leningrad, the people are parking their cars and campers in their drives, and opening their diaries, and calling up other people on the telephone. The deckchairs on the beach have been put away, and a weak sun shines on the promenade; there is fresh fighting in Vietnam, while McGovern campaigns ineffectually against Nixon. In the chemists' shops in town, they have removed the sunglasses and the insect-bite lotions, for the summer visitors have left, and have stocked up on sleeping tables and Librium, the staples of the year-round trade; there is direct rule in Ulster, and a gun-battle has taken place in the Falls Road. The new autumn colors are in the boutiques; there is now on the market a fresh intra-uterine device, reckoned to be ninety-nine per cent safe. Everywhere there are new developments, new indignities; the intelligent people survey the autumn world, and liberal and radical hackles rise, and fresh faces are about, and the sun shines fitfully, and the telephones ring. So, sensing the climate, some people called the Kirks, a well-known couple, decide to have a party."

It's the birthday of writer Margaret Landon, born in Somers, Wisconsin (1903). When she was 23, she and her husband signed up to be missionaries in Thailand, which was known as the Kingdom of Siam. For 10 years, Landon lived in Thailand, ran a school, and raised her three children. While she was living there, she came across a book by a woman named Anna Leonowens, a Welsh governess who had tutored the King of Siam's many wives and children during the 1860s. Landon was intrigued by her story, and she fictionalized it in a novel she titled Anna and the King of Siam (1944). Landon's book became a best-seller in 20 languages, selling more than a million copies. The story became even more famous when it was even more fictionalized into the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I (1956). Margaret Landon wrote one other novel, called Never Dies the Dream (1949), a fictionalized account of her own experiences in Thailand — but her own story was never as popular as Anna's.

It's the birthday of journalist and novelist Joe Klein, born in Queens in 1946. He was a respected political reporter when he decided to write a novel based on Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign. Although it was fiction, the characters were very thinly disguised. Clinton became Jack Stanton, and Hillary became Susan. Klein called the novel Primary Colors (1996), but he published it under the name "Anonymous," generating fevered speculation over the identity of the author. Washington insiders and experts pointed to Klein as the author, but he denied it over and over. Finally, when The Washington Post published a forensic handwriting analysis that linked Klein to the manuscript, Klein — wearing Groucho Marx glasses — held a press conference and admitted that he had written the novel and then lied about it. His fellow journalists were furious, but Primary Colors was a best-seller and made Klein a multimillionaire.

Primary Colors begins: "He was a big fellow, looking seriously pale on the streets of Harlem in deep summer. I am small and not so dark, not very threatening to Caucasians; I do not strut my stuff. We shook hands. My inability to recall that particular moment more precisely is disappointing: the handshake is the threshold act, the beginning of politics. I've seen him do it 2 million times now, but I couldn't tell you how he does it, the right-handed part of it — the strength, quality, duration of it, the rudiments of pressing the flesh. I can, however, tell you a whole lot about what he does with his other hand. He is a genius with it. He might put it on your elbow, or up by your biceps: these are basic, reflexive moves. He is interested in you. He is honored to meet you. If he gets any higher up your shoulder — if he, say, drapes his left arm over your back, it is somehow less intimate, more casual. He'll share a laugh or a secret then — a light secret, not a real one — flattering you with the illusion of conspiracy. If he doesn't know you all that well and you've just told him something 'important,' something earnest or emotional, he will lock in and honor you with a two-hander, his left hand overwhelming your wrist and forearm. He'll flash that famous misty look of his. And he will mean it."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

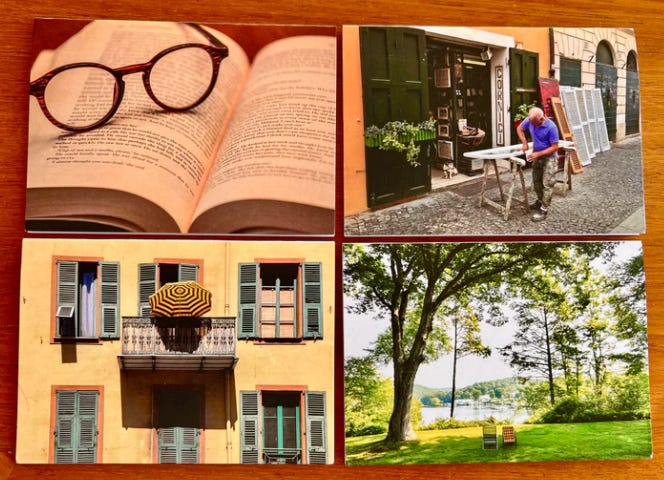

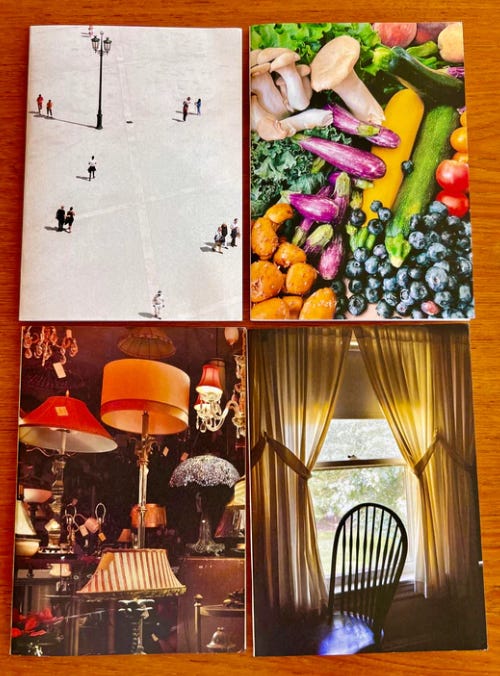

CHECK out our BRAND NEW notecards

Friendship Sonnets written by Garrison Keillor