TWA from Monday, May 15, 2017

“This Morning” by Mary Oliver from Felicity. © Penguin Press, 2016.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

The American poet Emily Dickinson died in Amherst, Massachusetts, on this date in 1886 . She had been in ill health for about two and a half years, and was confined to her bed for the last seven months of her life. Medical historians now believe that she was suffering from severe high blood pressure — she complained of headaches and nausea, and near the end of her life she struggled to breathe, eventually lapsing into a coma. She would not allow her doctor, Otis Bigelow, to come to her bedside, but would only consent to walk past the doorway. "Now, what besides mumps could be diagnosed that way!" he is said to have exclaimed. He listed her cause of death as "Bright's disease," which was a catchall diagnosis that included kidney disease as well as hypertension. Besides her physical ailments, she suffered greatly from the deaths of several close friends over the last years of her life; the most traumatic appears to have been that of her eight-year-old nephew in 1883.

Emily's friend and sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson wrote the poet's obituary for The Springfield Republican: "A Damascus blade gleaming and glancing in the sun was her wit. Her swift poetic rapture was like the long glistening note of a bird one hears in the June woods at high noon, but can never see." Dickinson had left specific instructions for her burial. Her casket was carried by the family's six Irish hired men, on a route that wound its way past her flower garden, through the barn in back of the house, and through a field of buttercups.

Very few of her nearly 1,800 poems were published during her lifetime, and what was published was done so anonymously. After her death, Dickinson's sister, Lavinia, discovered hundreds of poems that she had written over the years. The first volume, The Poems of Emily Dickinson, was published in 1890.

It was on this date in 1869 that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association. The 15th Amendment was being considered, granting voting rights to African-American men, but not to women. The women's suffrage movement was divided over whether to support the bill. One faction felt that any advancement in civil rights would eventually help women. But the other faction, led by Stanton and Anthony, opposed giving these rights to another group of men who, they felt, would then have no further interest in advancing the cause of women. They split from the American Equal Rights Association, forming their own national organization to be run by women.

Stanton and Anthony worked together for 50 years, and they made a good team. Anthony never married, so she was free to devote her life to the women's movement. Stanton wasn't free to travel for many years. She stayed home, raised the kids, did the research, and wrote the speeches that Anthony delivered.

Stanton once said, "I am the better writer, she the better critic [...] and together we have made arguments that have stood unshaken by the storms of thirty long years; arguments that no man has answered."

Today is the birthday of Lyman Frank Baum, born in Chittenango, New York (1856). He moved to Aberdeen, South Dakota, when he was 32, and opened up a general store called "Baum's Bazaar." He was popular with the neighborhood kids, telling them stories, all the while chomping on a cigar. He was also generous with his credit and the store went bankrupt. So he got a job as an editor for the local newspaper. He published his first book, Mother Goose in Prose, in 1897; it was a collection of stories based on traditional nursery rhymes. After that came Father Goose, His Book in 1899, but it was his 1900 novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, that we remember him for today. It was a critical and commercial success, and he went on to write 13 more novels based on the Land of Oz.

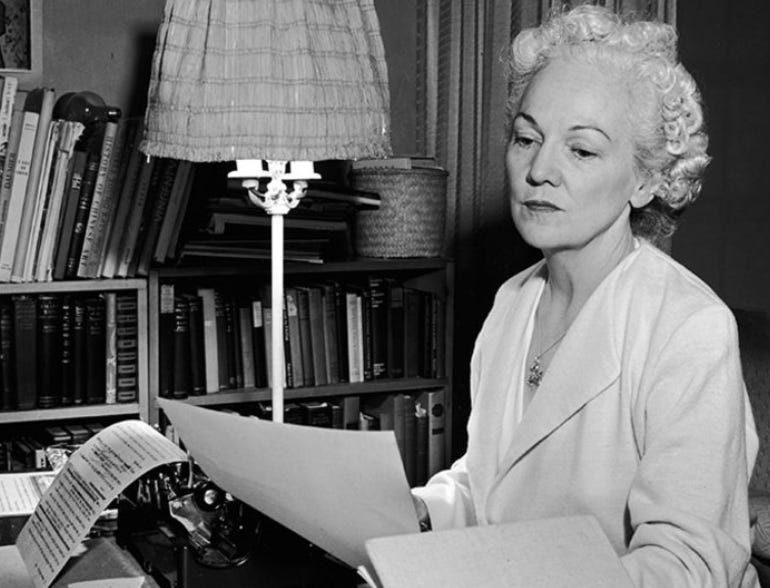

It's the birthday of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Katherine Anne Porter, born Callie Russell Porter in Indian Creek, Texas (1890). She was brought up by her beloved grandmother, Catherine Anne, whose name she later took. Porter grew up surrounded by books. She said: "All the old houses that I knew when I was a child were full of books, bought generation after generation by members of the family. Everyone was literate as a matter of course. Nobody told you to read this or not to read that. It was there to read, and we read." She especially loved Dante and Henry James.

There wasn't much money, or schooling, and Porter married at 16. Her husband was a drunk, and abusive, and she divorced him when she was 21. She moved to Chicago and got a job writing about movies, occasionally taking work as an extra. It was while writing for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver that she contracted the flu during the 1918 pandemic and spent months in the hospital recovering. When she was discharged, she was bald. When her hair started growing back, it came in white, and that's the way she kept it for the rest of her life.

Her first book, Flowering Judas and Other Stories, was published in 1930. Her next was a trilogy of short novels, Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1935), which garnered her considerable acclaim. For the next 30 years, she subsisted on money she earned from teaching, grants, selling short stories, and advances, while she worked on a novel about a group of characters sailing on a ship from Mexico to Germany. It took her 22 years to finish the book, which she called Ship of Fools. Whenever her publisher would ask about it, Porter would snap: "Look here, this is my life and my work and you keep out of it. When I have a book I will be glad to have it published."

Ship of Fools was finally published in 1962 and outsold every other book published that year. The film rights were sold for half a million dollars. Porter was able to live comfortably for the rest of her life. The film version (1965) was directed by Stanley Kramer and featured Vivien Leigh in her last film role.

Porter won the Pulitzer Prize (1966) for The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter.

Katherine Anne Porter said: "I have a very firm belief that the life of no man can be explained in terms of his experiences, of what has happened to him, because in spite of all the poetry, all the philosophy to the contrary, we are not really masters of our fate. We don't really direct our lives unaided and unobstructed. Our being is subject to all the chances of life. There are so many things we are capable of, that we could be or do. The potentialities are so great that we never, any of us, are more than one-fourth fulfilled. Except that there may be one powerful motivating force that simply carries you along, and I think that was true of me."

It was on this day in 1891 that Pope Leo XIII issued an official Roman Catholic Church encyclical addressing 19th-century labor issues. It's called Rerum Novarum, Latin for "Of New Things," and it is considered the original foundation of Catholic social teaching.

He said in the open letter that while the Church defends certain aspects of capitalism, including rights to private property, the free market cannot go unrestricted — that there is a moral obligation to pay laborers a fair and living wage.

He had much more to say to employers; first, he told them "not to look upon their work people as their bondsmen." He told them it was never OK to cut workers' wages. And he told them to "be mindful of this — that to exercise pressure upon the indigent and the destitute for the sake of gain, and to gather one's profit out of the need of another, is condemned by all laws, human and divine. To defraud any one of wages that are his due is a great crime which cries to the avenging anger of Heaven."

With these words Leo began a new chapter in the Catholic Church, one where social justice issues became incorporated into official Church doctrine, an essential part of faith, where the Church would stake out official positions and be vocal on issues like labor, war and peace, and the duties of governments to protect human rights.