“On Closing the Apartment of my Grandparents of Blessed Memory” by Robyn Sarah from Questions About the Stars. © Brick Books, 1998.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

Today is the birthday of Maria Mitchell, the first acknowledged female astronomer, born in 1818 on the island of Nantucket in Massachusetts. Although the American essayist Hannah Crocker explained that same year in her Observations on the Real Rights of Women that it was then a woman's "province to soothe the turbulent passions of men ... to shine in the domestic circle" and that "it would be improper, and physically very incorrect, for the female character to claim the statesman's birth or ascend the rostrum to gain the loud applause of men," Maria Mitchell's Quaker parents believed that girls should have the same access to education and the same chance to aspire to high goals as boys, and they raised all 10 of their children as equals.

Maria's early interest in science and the stars came from her father, a dedicated amateur astronomer who shared with all his children what he saw as physical evidence of God in the natural world, although Maria was the only child interested enough to learn the mathematics of astronomy. She would later say, in a quote recorded in NASA's profile of her, that we should "not look at the stars as bright spots only [but] try to take in the vastness of the universe," because "every formula which expresses a law of nature is a hymn of praise to God."

By age 12, Maria was assisting her father with his astronomical observations and data, and just five years later opened and ran her own school for girls, training them in the sciences and math. In 1838, she became the librarian of the Nantucket Atheneum and began spending her evenings in an observatory her father had built atop the town's bank.

On October 1, 1848, a crisp, clear autumn evening, Maria focused her father's telescope on a distant star. The light was faint and blurry, and Maria suddenly realized she was looking not at a star, but a comet; she recorded its coordinates, and when she saw the next night that the fuzzy light had moved, she was sure. Maria shared her discovery with her father, who wrote to the Harvard Observatory, who in turn passed her name on to the king of Denmark, who had pledged a gold medal to the first person to discover a comet so distant that it could only be seen through a telescope. Maria was awarded the medal the following year, and the comet became known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet."

Mitchell's list of firsts is impressive: She'd made the first American comet sighting; in 1848, she was the first woman appointed to the American Association for the Advancement of Science; in 1853, she became the first woman to earn an advanced degree; and in 1865, she became the first woman appointed to the faculty of the newly founded Vassar Female College as their astronomy professor and the head of their observatory, making her the first female astronomy professor in American history.

Mitchell also became a devoted anti-slavery activist and suffragette, with friends such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and helped found the American Association for the Advancement of Women. In her Life, Letters, and Journals, Maria declares that, "no woman should say, 'I am but a woman!' But a woman! What more can you ask to be? Born a woman — born with the average brain of humanity — born with more than the average heart — if you are mortal, what higher destiny could you have? No matter where you are nor what you are, you are a power."

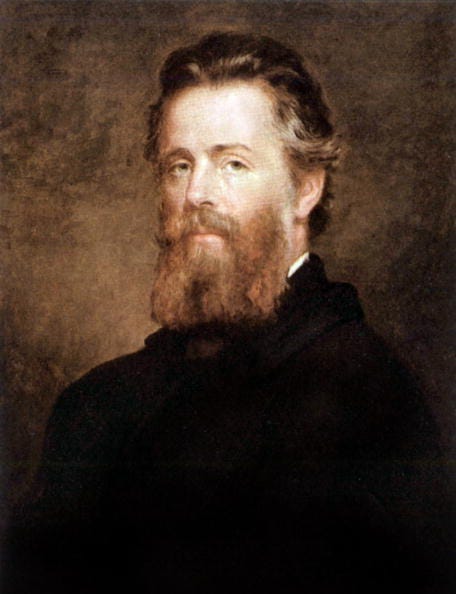

Herman Melville was born on this day in 1819 in New York City. The Melvilles were a family of Revolutionary War heroes and once-prominent merchants but, by young Herman's time, the family was in decline and the boy was raised in an atmosphere of financial instability and refined pretense.

In 1834, Melville left school to became a bank clerk, then tried farming and teaching, and in 1837 took to the sea for the first time as a cabin boy on a merchant ship bound for Liverpool with a hold full of cotton. Upon returning to New York, Melville held a series of unsatisfying jobs and decided to try his fortune in the West where for several months he saw the prairies, the western wilderness, the Mississippi headwaters and the Falls of St. Anthony but did not find a career. Melville returned to the east and in 1841 again signed up for the seafaring life, this time on the whaling shape the Acushnet, to cruise for whales in the Pacific for several years. Melville got more than he'd likely expected: The cruelties he experienced on the Acushnet, jumping ship in the Marquesas, being held in friendly if determined captivity by a band of Polynesians, escaping aboard an Australian whaler, which he also eventually jumped, and finally making his way to Hawaii and then back to the mainland.

When he returned in 1844, the 25-year-old Melville found an eager audience for his sailor's yarns, and he began writing a series of personal narratives on his adventures in Polynesia, on whaling, and on life as a merchant mariner. From these stories, Melville completed his first novel, Typee, which was partly based on his experiences as a captive. Although Melville's first attempt to publish his book was met with rejection on the grounds that the story couldn't possibly be true and was therefore of no value, once in print it was an instant best-seller and Melville quickly followed it with the equally popular Omoo.

In 1847, Melville married Elizabeth Shaw and the couple set up housekeeping in New York with Melville's younger brother and sister-in-law, their mother, and four of their sisters. Melville began work on his next novel, Mardi, although his living situation was not necessarily conducive to the easy production of a book, and his taste in reading shifted to include romantic novels — which he probably shared with his wife — a change of interest that can be seen in the fantastical, romantic conclusion of Mardi.

The Melvilles then settled into a farm near Pittsfield, Massachusetts. It was here, in 1850, that Melville would meet Nathaniel Hawthorne, whom Melville would come to think of as a dear friend and confidant. The following year, after an intoxicating period of exploring the ideas of transcendentalism and allegorical writing, Melville penned his enduring masterpiece, Moby Dick, the lyrical, epic story of Ahab and the infamous white whale, dedicating it to Hawthorne in "admiration for his genius." Moby Dick was met with mixed reviews. The London News declared Melville's power of language "unparalleled," while the novel was criticized elsewhere for its unconventional storytelling, and Melville's fans were disappointed not to find the same kind of adventure story they had loved in Typee and Omoo. It was the beginning of the end of Melville's career as a novelist and, following a series of literary failures, he turned to farming and writing articles to support his family.

When the family returned to New York City in 1863, Melville became a customs inspector and began a second literary life as a poet, drawing on the emotional impact of the Civil War. His first book of poetry was Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, which was praised in numerous American newspapers and magazines, but Melville was never again to rise to the prominence he'd experienced at the beginning of his career, and his ensuing stories and poems were largely ignored, including the posthumously published novel, Billy Budd.

It took readers until the 1920s to catch up to the prose, style, and power of Moby Dick. But once they did, appreciation never again lagged, and Melville's masterpiece is now regarded as one of the greatest novels ever written.

Melville recognized the intelligence of whales in Moby Dick, just as we today admire the sensitivity of our pets.

I have not read Moby Dick or any of Herman Melville's literature. I've head some positive reviews of Billy Budd. I do try to consider perusing the great classics a few times a year. I am intrigued in the unconventional storytelling style of Mr. Melville. I wonder if I should consider Nathaniel Hawthorne as well. Thanks.