TWA from Tuesday, September 12, 2017

“Last Night I Was a Child Again in Raleigh” by Corey Mesler from Among the Mensans. © Iris Press, 2017.

ORIGINAL TEXT and AUDIO - 2017

It's the birthday of the journalist and editor H.L. (Henry Louis) Mencken, born in Baltimore, Maryland (1880). He graduated as the valedictorian from his high school at the age of 15, but even though he was burning to write, he did exactly what his father expected: He took a job at the cigar factory. He started out rolling the cigars alongside the other blue-collar men, and he actually enjoyed that manual labor. But when he was promoted to the front office, he was hopelessly bored. He finally mustered up his courage and told his father that he wanted to pursue a career in journalism. His father told him to bring up the subject again in a year.

Mencken had been working at his father's factory for three years when, on New Year's Eve in 1898, his father had a convulsion and collapsed. His mother told Mencken to get a doctor, 11 blocks down the street, and Mencken later said, "I remember well how, as I was trotting to [the doctor's] house on that first night, I kept saying to myself that if my father died I'd be free at last."

His father died two weeks later. The day after his father's funeral, Mencken shaved his face, combed his hair, put on his best suit, and went down to the Baltimore Morning Herald, asking for a job. Mencken came back every single day for the next four weeks. He finally wore the editor down, and he got to write two articles, each fewer than 50 words long.

He went on to become one of the most influential and prolific journalists in America, writing about all the shams and con artists in the world. He attacked chiropractors and the Ku Klux Klan, politicians and other journalists. Most of all, he attacked Puritan morality. He called Puritanism, "the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy."

At the height of his career, he edited and wrote for The American Mercury magazine and the Baltimore Sun newspaper, wrote a nationally syndicated newspaper column for the Chicago Tribune, and published two or three books every year. His masterpiece was one of the few books he wrote about something he loved, a book called The American Language (1919), a history and collection of American vernacular speech. It included a translation of the Declaration of Independence into American English that began, "When things get so balled up that the people of a country got to cut loose from some other country, and go it on their own hook, without asking no permission from nobody, excepting maybe God Almighty, then they ought to let everybody know why they done it, so that everybody can see they are not trying to put nothing over on nobody."

When asked what he would like for an epitaph, Mencken wrote, "If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl."

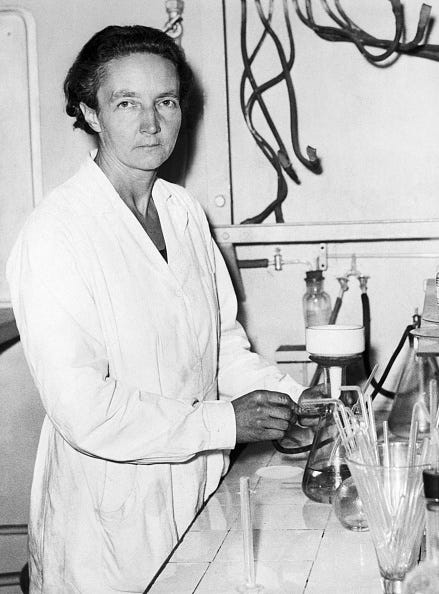

Today is the birthday of French scientist Irène Joliot-Curie, born in Paris (1897). She was the daughter of Pierre and Marie Curie. She was homeschooled as part of an educational experiment run by her parents and their friends. Called "The Cooperative," the adults — all experts in their respective fields — took turns teaching one another's children. She then studied at the Sorbonne, but World War I interrupted her university career, so she helped her mother operate mobile X-ray units in field hospitals instead.

She began assisting her mother in the lab at the Institute of Radium at the University of Paris when she was 21. That's where she met a young chemical engineer named Frédéric Joliot; they were married in 1926, and in 1935, the husband and wife team won the Nobel Prize in chemistry, for artificially creating radioactive elements. Unfortunately, like her mother, Joliot-Curie developed leukemia as a result of her close work with radioactive substances; she died in 1956, at the age of 58.

Physicist James Chadwick wrote of her: "She knew her mind and spoke it, sometimes perhaps with devastating frankness; but her remarks were informed with such regard for scientific truth and with such conspicuous sincerity that they commanded the greatest respect in all circumstances."

Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning eloped on this date in 1846. They had been courting in secret for a year and a half, through the mail, unbeknownst to her father. It had begun when Browning wrote Barrett a gushing fan letter, saying, "I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett ... and I love you too." She wrote a long letter in return, thanking him and asking him for ways she might improve her writing. Barrett was an invalid, and was reliant on morphine, and it was some months before Browning convinced her to meet face to face. Barrett's father didn't like Browning, and viewed him as a fortune hunter.

On the day of the wedding, Browning posted another letter to Barrett, which read, "Words can never tell you, however, — form them, transform them anyway, — how perfectly dear you are to me — perfectly dear to my heart and soul. I look back, and in every one point, every word and gesture, every letter, every silence — you have been entirely perfect to me — I would not change one word, one look." They were married at St. Marylebone Parish Church, and Barrett returned to her father's house, where she stayed for one more week before she ran off to Italy with Browning. She never saw her father again. After the wedding, she presented Browning with a collection of poems she'd written during their courtship. It was published in 1850 as Sonnets from the Portuguese.