TWA from Sunday, September 10, 2017

“The Kingfisher” by Mary Oliver from Devotions. © Penguin Press, 2017.

ORIGINAL TEXT and AUDIO - 2017

It’s the birthday of best-selling poet Mary Oliver, born in Maple Heights, Ohio (1935). As a child, she spent most of her time outside, wandering around the woods, reading and writing poems.

Oliver went to college in the ’50s at Ohio State University and Vassar, but dropped out. She made a pilgrimage to visit Edna St. Vincent Millay’s 800-acre estate in Austerlitz, New York. The poet had been dead for several years, but Millay’s sister Norma lived there along with her husband. Mary Oliver and Norma hit it off, and Oliver lived there for years, helping out on the estate, keeping Norma company, and working on her own writing. In 1958, a woman named Molly Malone Cook came to visit Norma while Oliver was there, and the two fell in love. A few years later, they moved together to Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Oliver said: “I was very careful never to take an interesting job. Not an interesting one. I took lots of jobs. But if you have an interesting job you get interested in it. I also began in those years to keep early hours. [...] If anybody has a job and starts at 9, there’s no reason why they can’t get up at 4:30 or 5 and write for a couple of hours, and give their employers their second-best effort of the day — which is what I did.”

She published five books of poetry, and still almost no one had heard of her. She doesn’t remember ever having given a reading before 1984, which is the year that she was doing dishes one evening when the phone rang and it was someone calling to tell her that her most recent book, American Primitive (1983), had won the Pulitzer Prize. Suddenly, she was famous. She didn’t really like the fame — she didn’t give many interviews, didn’t want to be in the news. She once wrote in an introduction to a poetry collection, “I have felt all my life that I was wise, and tasteful, too, to speak very little about myself — to deflect the curiosity in the personal self that descends upon writers, especially in this country and at this time, from both casual and avid readers.”

When editors called their house for Oliver, Cook would answer, announce that she was going to get Oliver, fake footsteps, and then get back on the phone and pretend to be the poet — all so that Oliver didn’t have to talk on the phone to strangers, something she did not enjoy. Cook was a photographer, and she was also Oliver’s literary agent. They stayed together for more than 40 years, until Cook’s death in 2005.

Oliver said: “I’ve always wanted to write poems and nothing else. There were times over the years when life was not easy, but if you’re working a few hours a day and you’ve got a good book to read, and you can go outside to the beach and dig for clams, you’re okay.”

Oliver’s books of poems include No Voyage (1963), The River Styx, Ohio, and Other Poems (1972), Twelve Moons (1978), The Leaf and the Cloud (2000), Owls and Other Fantasies (2003), Red Bird (2008), Dog Songs (2013), and Velocity (2015). Her most recent collection, Devotions, comes out in October of this year.

It’s the birthday of naturalist and science writer Stephen Jay Gould, born in New York City (1941). When he was a boy, he was fascinated by garbage trucks and decided that he wanted to be a garbage collector so he could examine all of the strange things that people throw away. But after he saw his first dinosaur skeleton at the Museum of Natural History, he decided to become a paleontologist instead.

He became famous for his monthly columns in Natural History magazine, which were collected in books like The Panda’s Thumb (1980) and The Flamingo’s Smile (1985). He liked to write about the messy randomness of evolution. He was one of the best-known popular science writers because he used analogies that anyone could understand. In his book Full House (1996), he used the history of baseball batting averages to explain the evolution of large animals. He wrote about everything from the changing face of Mickey Mouse, to the inefficiency of IQ tests, to his own cancer. He loved the fact that when he was diagnosed with cancer, the average life expectancy was eight months, and he lived for 20 more years. He wrote an article about it, exploring the many meanings of the word average. He died on May 20, 2002.

Stephen Jay Gould said, “Homo sapiens [are] a tiny twig on an improbable branch of a contingent limb on a fortunate tree.”

It’s the birthday of editor and essayist Cyril Connolly, born in Whitley, England (1903). He was one of the most important English literary critics and edited the literary journal Horizon from 1940 to 1950, publishing authors like W.H. Auden and George Orwell. As a young man, he described himself as “dirty, inky, miserable, untidy […] a coward at games, lazy at work, unpopular with my masters and superiors, anxious to curry favour and yet to bully whom I dared.” He said that he drifted into being a literary critic through unemployability. Even though he became one of the best book reviewers in England, he always hated it. He said, “I review novels to make money, because it is easier for a sluggard to write an article a fortnight than a book a year.” Someone once asked W.H. Auden who was the best book critic alive and Auden said, “Cyril Connolly, alas.”

He published one novel, The Rock Pool (1936), but he thought it was so bad that he decided never to write fiction again. Instead, he wrote two great books about the misery of not being able to write great books, The Enemies of Promise (1938) and The Unquiet Grave (1944).

He wrote, “The true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece […] no other task is of any consequence.”

It’s the birthday of Czech poet and novelist Franz Werfel, born in Prague (1890). He was one of the most important members of the German Expressionists, who wrote about inward emotions instead of outward reality.

His father was a Jewish glove maker, but his nanny was Catholic and she often secretly took him to Catholic masses. He became obsessed with religion as a boy, and he built altars and performed religious ceremonies in his bedroom. For the rest of his life he was torn between Judaism and Christianity, and he was always fighting with his father. When his father tried to make him work at the family glove factory, he stole important accounting documents from the office and flushed them down the toilet. He ran away and hung out at cafés with writers like Max Brod and Franz Kafka. He wrote his first book of poems, The Philanthropist (1911), about his hope that human beings could get along despite the increasing tensions in Europe. He wrote, “My one and only wish, O Man, is to be thy brother!”

After serving in World War I, he became a pacifist and got arrested for reciting anti-war poems in a café. He began to write historical fiction, and in 1933 he came out with his most famous novel, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh. It was the first novel about the genocide of the Armenians by the Turks. It was published around the world. It became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection in the United States, even though the U.S. government pressured the translator to delete hundreds of passages that were too inflammatory.

Werfel was living in France when the Nazis came to power. He had to go underground and burn all the manuscripts he had been working on because they were too dangerous to carry. He was hiding out for several weeks in Lourdes [Loord], France, where he heard the story of St. Bernadette, the 14-year-old girl who had seen visions of the Virgin Mary. Werfel vowed that if he escaped the Nazis, he would write his next novel about the girl. When he reached the United States, he wrote The Song of Bernadette (1941), and it became a best-seller.

Franz Werfel said, “Religion is the everlasting dialogue between humanity and God. Art is the soliloquy.”

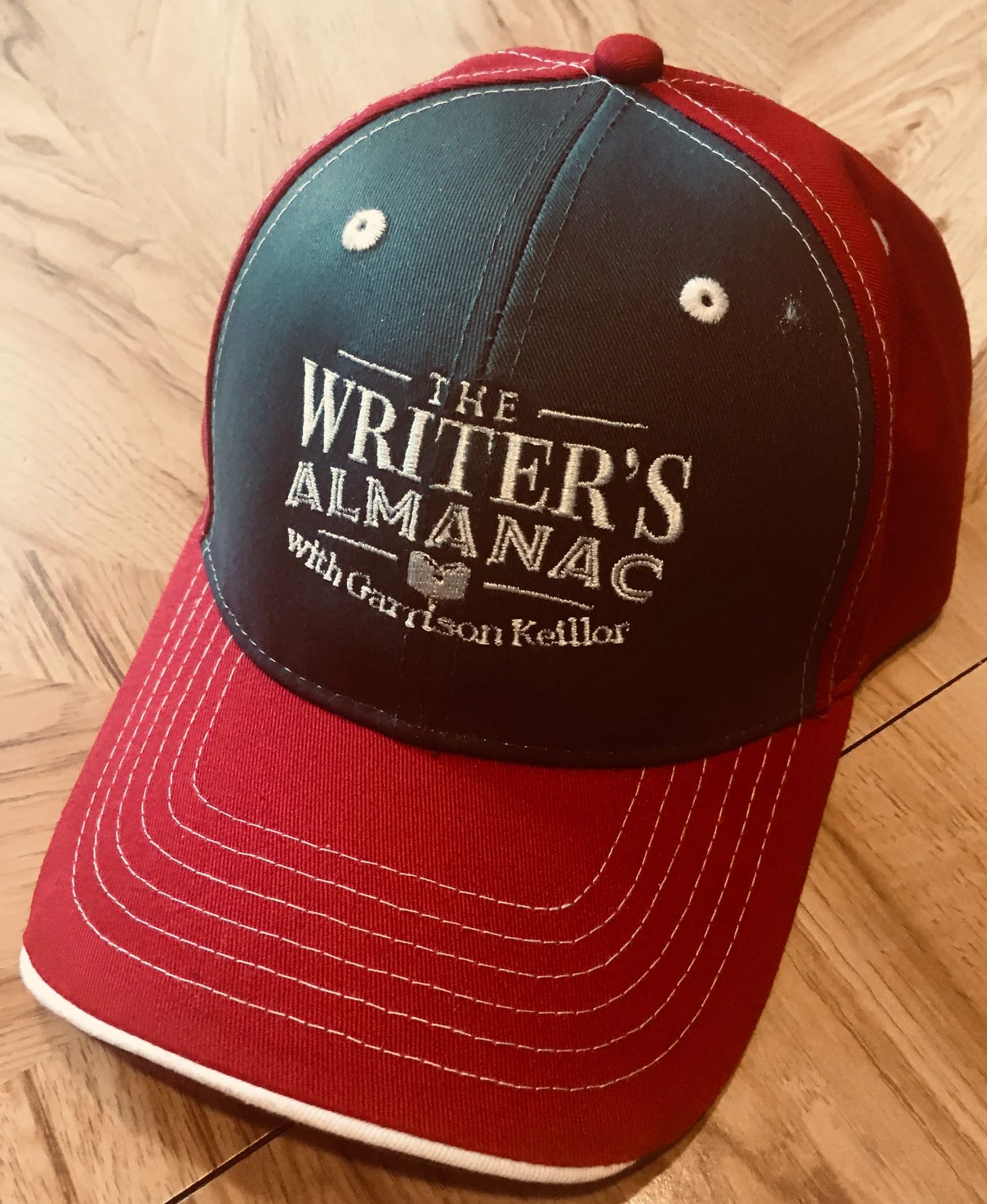

Considering that you grew up in the Midwest and that you are one of the best writers around, I am shocked, shocked, shocked, you refer to the headgear you are selling as a hat. It is a cap, not a hat. A hat has a brim that goes all around. A cap only has a beak! Before I retired I ran an advisory firm that served agribusiness entities. In the process I accumulated a collection of some 1,500 caps from around the world. One of my mentors was the late Tom Burrus, co-owner of Burrus Seed, Arenzville, IL who taught me the difference. In any case, TWA is the most civilized way of greeting the morning. And yes, I will buy one of your caps!